Space Exploration: Garrett Biggs

Astronauts perform some strange superstitions before they shoot off into orbit to explore the vast expanses of space. NASA commanders play cards with the tech crew the night before a launch, continuing until the commander loses a hand. Russian cosmonauts pee on the right rear tire of their transfer bus on the way to a launch. These are strange quirks, but they are crucial for these space-explorers to feel comfortable before and during a mission.

Writers also have rituals that must be performed in order to shake off bad vibes and get into a zone where they feel comfortable putting words on a page. When we read a great book, we only see the final product, and not the obsessive care put into the work environment that allowed for its creation. In SPACE EXPLORATION, our goal is to demystify writers’ environments and explore the ways in which they’ve been created and curated, and how they affect the mental spaces of the authors who inhabit them.

We asked writers to tell us about their necessary spaces; the physical spaces as well as the desired headspace to write. We asked about their rituals— special meals that have to be eaten pre-writing sesh, only writing in purple ink, lucky pieces of clothing that may have once inspired a particularly powerful passage. We asked them to engage our senses and tell us which aspects of process must be deliberate and what is arbitrary. These are the spaces they shared with us.

Our third feature was written by Garrett Biggs managing editor of The Adroit Journal.

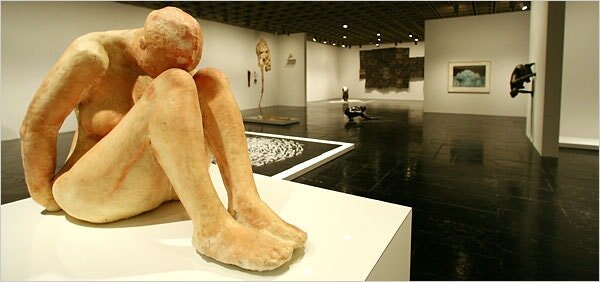

“Untitled” (1992) by Kiki Smith

Writing on the Skin

1.

This is for the beetle I killed in the writing of my first novel, but it’s also for my mother who I speak on the phone with once a day. And since first novels (unlike beetles) possess weak exoskeletons and are crushed rather easily, I’ll throw in one more dedication for the aluminum dinner chair I set in front of my writing desk, because who knows if I’ll get another chance to acknowledge its importance in the drafting process.

2.

I struggle to admit that I have never had a physical relationship with my writing. This is in spite of having always romanticized the idea of a corporeal writing practice. Think: Suzan-Lori Parks telling us to “dance while we write.” Or think: Clarice Lispector most likely transcending the human body altogether in order to create Agua Viva. We have stories of writers running, writers fucking, writers eating, writers stripping to their underwear, writers doing whatever it takes to be able to inch a little closer to the subject of the human body. Only recently have I come to understand that we rarely consider the opposite: those who struggle to materialize bodies on the page, because to some extent, these bodies remain uncharted spaces. Writing what you know is a near-useless truism, sure, but I don’t know how to write about life on Gliese 832 c (an extrasolar planet orbiting a red dwarf star) and I don’t know how to write about my weird, arthritic wrists. Sorry.

3.

Problem is, I have to. And if there was one consistent note I received in the drafting of my book, it’s that I needed to write a more embodied narrative. In spite of no lack of effort on my part, my characters often materialize with no physical characteristics. They come into their world with no pimples or sweat or vomit or hair; they are at first dull and hazy. While at one time I might have chalked this up to some kind of deliberate aesthetic effort, juggling 200 pages of narrative has a tendency to make you more honest. Eventually in the drafting of my book I had to admit that I had an issue: It really was a lack of effort on my part. If I was going write this novel well, I would have to attune my writing to the body.

4.

I have good news and bad news. The good is that this shouldn’t be read as romantic. No one here learns to love or even tolerate the body they are in. The bad is I did at one point attend a spin class with fifty or so white ladies in Lululemon sportswear, vomiting on a tile bathroom floor because I “turned it up” too quickly.

5.

The incident at spin class taught me a lot about bodily fluids, but so too did the work of Kiki Smith. Smith may be best known for her fabulist sketches, but her bronze casts of disembodied organs are perhaps more useful when thinking of the relationship between body and narrative. She is notable for having a long-standing engagement with corporeality as a subject, calling attention to its most overlooked aspects. In her sculptures, the body is presented in equal parts as a sexual object, as well as a place to project political and social ideologies. It’s a powerful attempt to reclaim the corporeal form, but what strikes me most is how helpless the sculptures appear. In spite of being arresting images, the body remains a vulnerable space—something uncomfortable and uncertain.

6.

It’s into this discomfort that I wrote. Or continue to write, really. In an effort to remain aware of the body throughout the drafting process, I have arranged my writing space accordingly. Mirrors are stacked above the books on my desk. Craft books have been replaced with texts on anatomy. I post photographs of Smith’s sculptures on the wall. When I sit down to write, I don’t remove the shoes from my feet. I work not from an ergonomically-correct office chair, but instead from an especially uncomfortable aluminum dining chair. The thing is I want my writing to become a somewhat painful process. I want to become more aware of the burning in my lower spine; the ache of my bony ass; the sweat pooling at the bottom of my feet.

7.

There is privilege here, I am certain. After all, my body is young. My body is healthy. My body’s shape and size and color allow me to move through the world with relative ease. Perhaps this is all the more reason to practice an attention to the body, though: That we who have the privilege to forget or ignore the bodies we inhabit should become more cognizant of them, uncomfortable as they may be.

8.

In Selah Saterstrom’s Ideal Suggestions: Essays in Divinatory Poetics, she writes that “narrative orchestrations that collaborate with uncertainty work in varied ways through the live wires tucked within a reader.” Narrative orchestrations collaborating with discomfort may potentially do the same. An awareness of one’s physicality whilst drafting opens the door for interruptions—it allows an element of chance, of randomness to enter a text. Which brings me to my only regret thus far: The aforementioned beetle I would dedicate the book to, were it published today. When it first crawled on my desk in the summer of 2018, I instinctively leapt to kill it. Didn’t think it would mean much: writhing beneath a wad of tissue, the pressure of my hands. Writing can be an act of violence too, but I didn’t see its wings until after.

9.

I worry it wouldn’t have changed much if I did.

Garrett Biggs's recent work appears in Black Warrior Review, The Offing, and Chicago Review of Books, among other publications. He is managing editor of The Adroit Journal, and an MFA candidate in fiction at the University of Colorado Boulder, where he teaches creative writing. More of his writing can be found at garrettbiggs.net