Space Exploration: Brian Oliu

Astronauts perform some strange superstitions before they shoot off into orbit to explore the vast expanses of space. NASA commanders play cards with the tech crew the night before a launch, continuing until the commander loses a hand. Russian cosmonauts pee on the right rear tire of their transfer bus on the way to a launch. These are strange quirks, but they are crucial for these space-explorers to feel comfortable before and during a mission.

Writers also have rituals that must be performed in order to shake off bad vibes and get into a zone where they feel comfortable putting words on a page. When we read a great book, we only see the final product, and not the obsessive care put into the work environment that allowed for its creation. In SPACE EXPLORATION, our goal is to demystify writers’ environments and explore the ways in which they’ve been created and curated, and how they affect the mental spaces of the authors who inhabit them.

We asked writers to tell us about their necessary spaces; the physical spaces as well as the desired headspace to write. We asked about their rituals— special meals that have to be eaten pre-writing sesh, only writing in purple ink, lucky pieces of clothing that may have once inspired a particularly powerful passage. We asked them to engage our senses and tell us which aspects of process must be deliberate and what is arbitrary. These are the spaces they shared with us.

This feature is written by Brian Oliu, whose collection of essays entitled Body Drop: Notes on Fandom and Pain in Professional Wrestling will be published by The University of North Carolina Press in 2021.

One of my favorite questions I ask of all of my students is if they have any work or writing rituals—I mention Proust’s name and sound fancy, telling them the story of the madeleine and how Alabama’s dear mercurial coach Nick Saban has a similar routine: a cup of coffee and two Little Debbie Oatmeal Cream Pies every morning before he starts his day of poring over defensive schemes. We talk music or no music, of snacks, midnight or early morning. I teach a lot of freshmen, so a lot of the responses are that they find themselves in flux—learning new patterns on how to work, or dealing with no parents but an awkward pizza roll microwaving roommate. It is a lot of “I used to, but now…” with a lot of nodding fellowship from their cohort.

I like to think that I am a writer who responds well to patterns. There are some constants in my work—Microsoft Word, Baskerville, all browser tabs open because if I were to close them, it would put too much pressure on the writing, so yes, Twitter has to stay open so I don’t fool myself into thinking I am crafting something I am not. I am very sensitive to sound, so it either has to be silent or constant—a murmur of a coffeeshop or a soundscape of a rainforest is fine, but song lyrics or television dialog is not. I will lose minutes upon minutes eavesdropping.

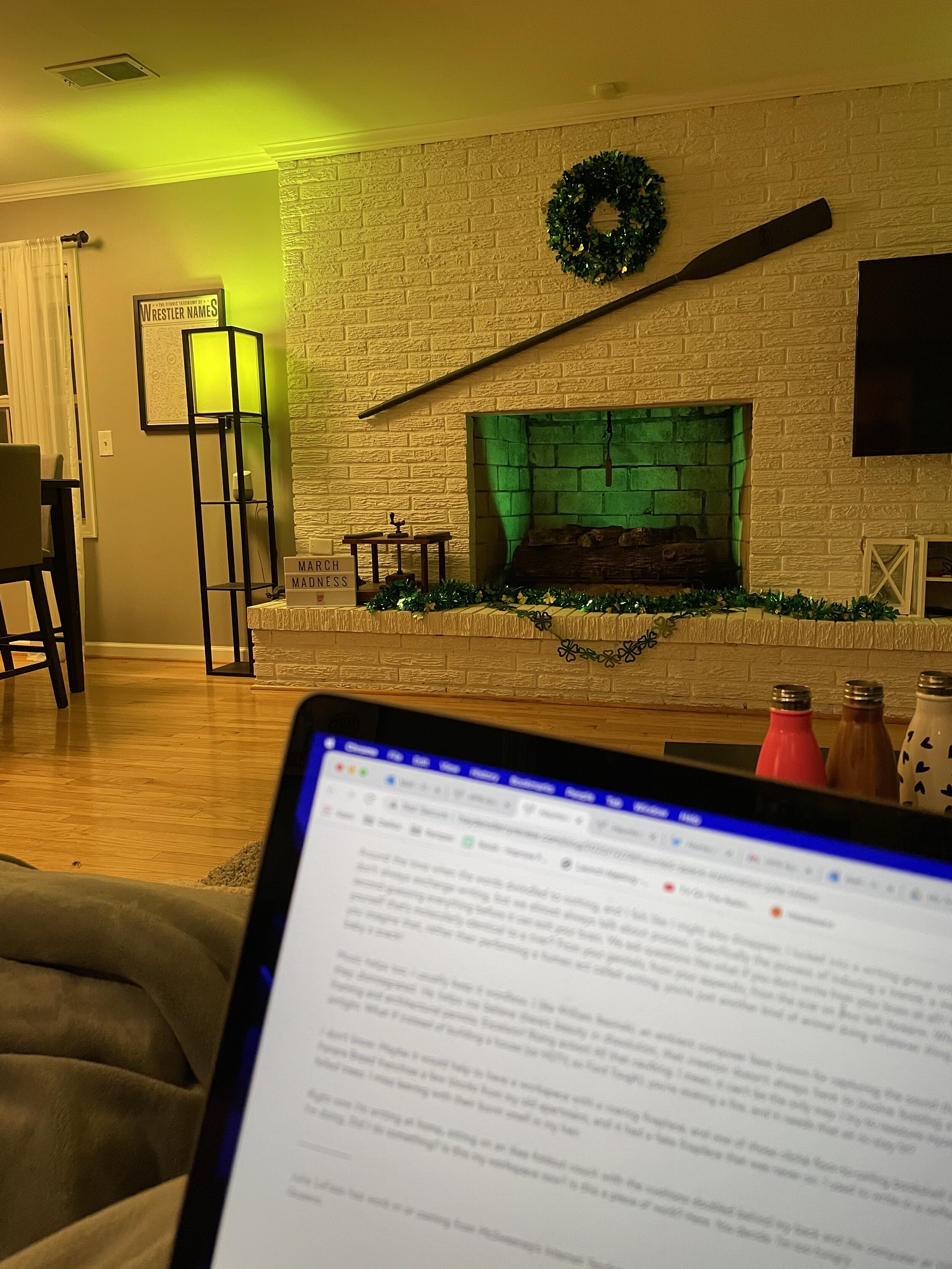

Here in Tuscaloosa, I used to run a reading series that often read in untraditional spaces: nature preserves, bars where there was no stage, backrooms of breweries. One thing that was always necessary was to “define the space”—to make the person sitting in the back of the bar come forward to designate the “new back of the bar,” to make the space our own. I find this is the best technique I can come up with for my own writing process. This isn’t to say that I can write anywhere, but I can essentially “set up camp” anywhere. During the pandemic, I have found myself lamenting the act of writing in coffeeshops, mostly because it made me designate a space—it is much harder to do this while at home, because, essentially, all space has become “working space” and therefore none of it is. Here, now, I am writing on my spot on the couch with a Diet A&W Root Beer, and my feet up on the coffee table. It is the same spot I find myself watching Wednesday Night Dynamite, or eating something I threw together in a slow cooker. It is not my ideal writing space, but nothing about writing right now seems particularly ideal. I have done my best to define this space with the space that I have.

I have made a lot of “pandemic purchases” that have gotten me through the past year: a new GPS watch, new sheets, an adoption fee for a retired racing greyhound. But two of the best are $100 for a local company to come and power wash our back screened in porch of all of the muck and pollen that accumulates over the Alabama spring, and a folding card table at Lowe’s that sits on said porch, effectively creating an outside office that got me through the summer. Even the act of “going outside to work,” was refreshing—a space to give myself permission to do something other than what was expected of me: lesson planning, copywriting, endless doom-scrolling on Twitter. This is where I finished the edits for my forthcoming book, “Body Drop: Notes on Fandom and Pain on Professional Wrestling,” sweating in the Alabama heat alongside my to-go Dunkin iced coffee, leaving pools of water whenever we stayed in the same position for too long.

This, in turn, reminded me of finishing the book the previous summer—writing exclusively about pain and discomfort as I sat in a busy Starbucks with my legs tucked underneath the back of the chair as pain radiated down them. I later recognized that this excruciating pain was caused, in part, by the chairs of the Starbucks—a quick search confirmed this, by stating that in a high-volume Starbucks, the chairs are meant to be purposely uncomfortable in order to create higher turnover. Of course, this is to be expected, but when writing a book on pain, persevering through it all was a common theme, and therefore my stubbornness kept me there for hours at a time, even as I felt the backs of my Achilles go numb.

I, of course, miss it. I certainly don’t want to return to the pain, and the book, thankfully, is finished—but I miss having a designated space for each of my projects. I can tell you the spaces that I associate with all of my books: a bright green-painted room was the backdrop for my undergraduate thesis that was written in computer coding language, the green of the walls seeping into the green text nightmare that is associated with MS-DOS. The small room with the desk and the bed where I wrote small pieces about missed connections, each essay contained in the comment box of the website, myself contained in the room with the door closed and the lights off—a little drunk and a lot lonely. The book on basketball on a round hand-me-down wooden table with a split in the middle that looked like the top of the key. A book on video games edited at my parents’ dining room table—all ornate and tablecloth and chandelier, the words full of gloss and glitter, forever dramatic in its excess.

My current writing project is one that I have been working on for almost ten years—a book about running, about being in constant motion. It is a book that I find myself wanting to get perfect, so I find myself simply not writing, or, at best, finding moments where I can squirrel things away; a sentence here, or an idea there in those times where I can distract myself from thinking that I am actually writing the thing. It is an endless task—a true marathon, though marathons end; I know, I have seen the end of them. Perhaps it is a book that needs to be done like this—something in constant motion. Or, there is simply not a space that exists for it yet to exist; a search that will continue on long after the folding table is leaned up against the side of the brick, or my back has been properly stretched, or the paint on the walls have dried. I hope that one day the work will be the one to define the space, lay it out for me, welcome me internally and externally. I hope there is coffee there, a comfortable chair, an air vent that does not blow on me to distract me from whatever it is I am easily distracted from. The words will simply just be there.

Brian Oliu teaches, writes, and fights out of Tuscaloosa, Alabama. His publications include three chapbooks and five full-length collections of nonfiction, ranging on topics from Craigslist Missed Connections, to computer viruses, to the arcade game NBA Jam. He has two projects forthcoming in 2021: a collaborative chapbook on the Rocky films with the poet Jason McCall, “What Shot Did You Ever Take,” by The Hunger Press, and a full-length collection of essays, “Body Drop: Notes on Fandom and Pain in Professional Wrestling” by The University of North Carolina Press. You can preorder Body Drop here.