Review of The Sky Was Once A Dark Blanket by Kinsale Drake

Kinsale Drake is a Diné poet/editor/playwright whose work has appeared in Poetry, Best New Poets, Poets.org, Poetry Northwest, The Slowdown, Black Warrior Review, The Adroit Journal, Poetry Online, Yale Literary Magazine, TIME, NPR, MTV, and elsewhere. Her debut collection, The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket (University of Georgia Press, 2024), won the 2023 National Poetry Series.

Kinsale Drake’s debut collection of poetry The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket is flush with music, dance, remembrance and family, pop culture, and joy, which “will come, / like the frogs, / more often.” The speaker takes us through desert landscapes—wind-touched sagebrush, rocks that glow at night, yucca plants, uranium mines, cholla, dammed rivers, and saguaro—as well as the landscape of memory and lineage. At its core, Drake’s enchanting debut collection is an outstretched hand, holding in its palm love and admiration for the people and places that make us, and a call to continue singing—to continue, continue, continue.

We begin with song, or more accurately, the rejection of one. In “spangled,” which opens the collection, the speaker says, “enough about you.” Instead, Drake writes:

I must sing

the hum of the yucca

and icy heartbeat

of river. I must sing

our grandparents’ blues

knocked down in the grasses

and thick in the farmhouse.

O, like Jimi’s guitar I must sing—

dirty sing blister let the sound

rip the sky

rush of birds spooked

from deep in our throats—

our song:

This collection is dedicated to musicality and throughout considers how song can connect us to memory, place, sensation, and those we love. Within “spangled” this attention to sonics and sound is visible: at the start of the poem, the consonance of [m] creates a soft humming in our throats, just like a guitar being strummed, until after the mention of Jimi Hendrix, where the assonance of [i] and sharpness of “dirty sing blister” shifts and quickens the poem. The continuous enjambment at “sing” has created its own chorus of light, breathless sound, that in the last few lines is upset by the repetition of the [o] noise that crafts a sense of relief as we reach the last line.

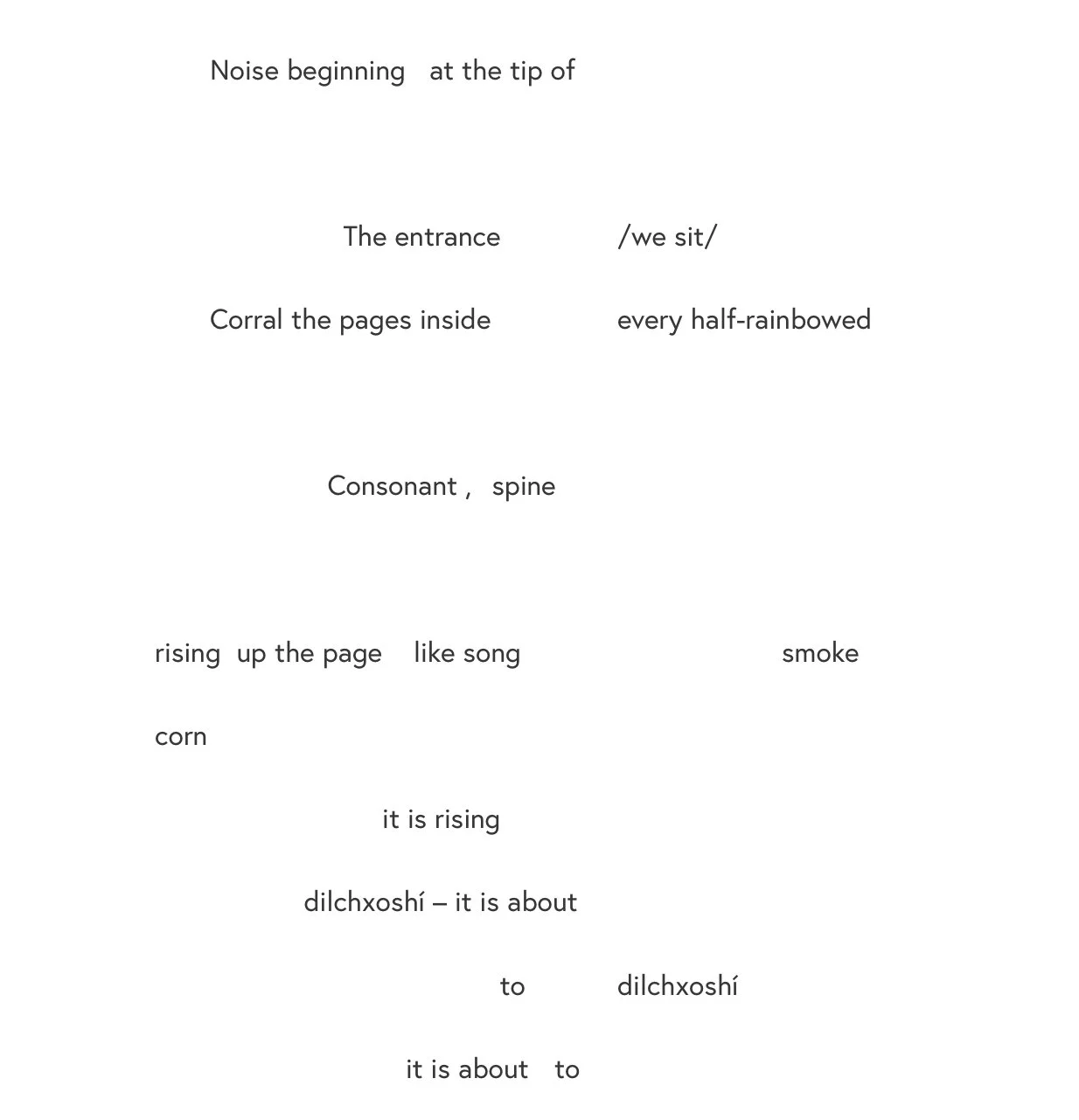

Another place in which the writing swells with rhythm and beat is in “Navajo-English Dictionary,” where the way Drake utilizes white space feels like a breath-taking, like a singer getting ready to belt.

Music acts as a portal, allowing the poet to slip through time and space. Thinking of her mother who “used to sneak out to border towns / to dance with cowboys” and grandmother who has a “face just softened by the rainbow of a smile,” she tells us: “When I want to call up / the memory of these women, I sit / with the familiar orchestra / of scratched up CDS.” The musical interests of the work spans genres and periods—from the Jimi Hendrix nod above to jazz singer Mildred Bailey to country singers Hank Willaims and Patsy Cline and even to emo/punk band My Chemical Romance. In the stories the speaker carries to the page, the voices of others slip in—her mother at a table with a puzzle, her girl who tells jokes in the car—and she asks, “How do I start a story I never lived?” Yet, this collection is stunning for its remembering, for its language that hums fully, in what Drake writes, is “our song”—the music of all the voices collected here.

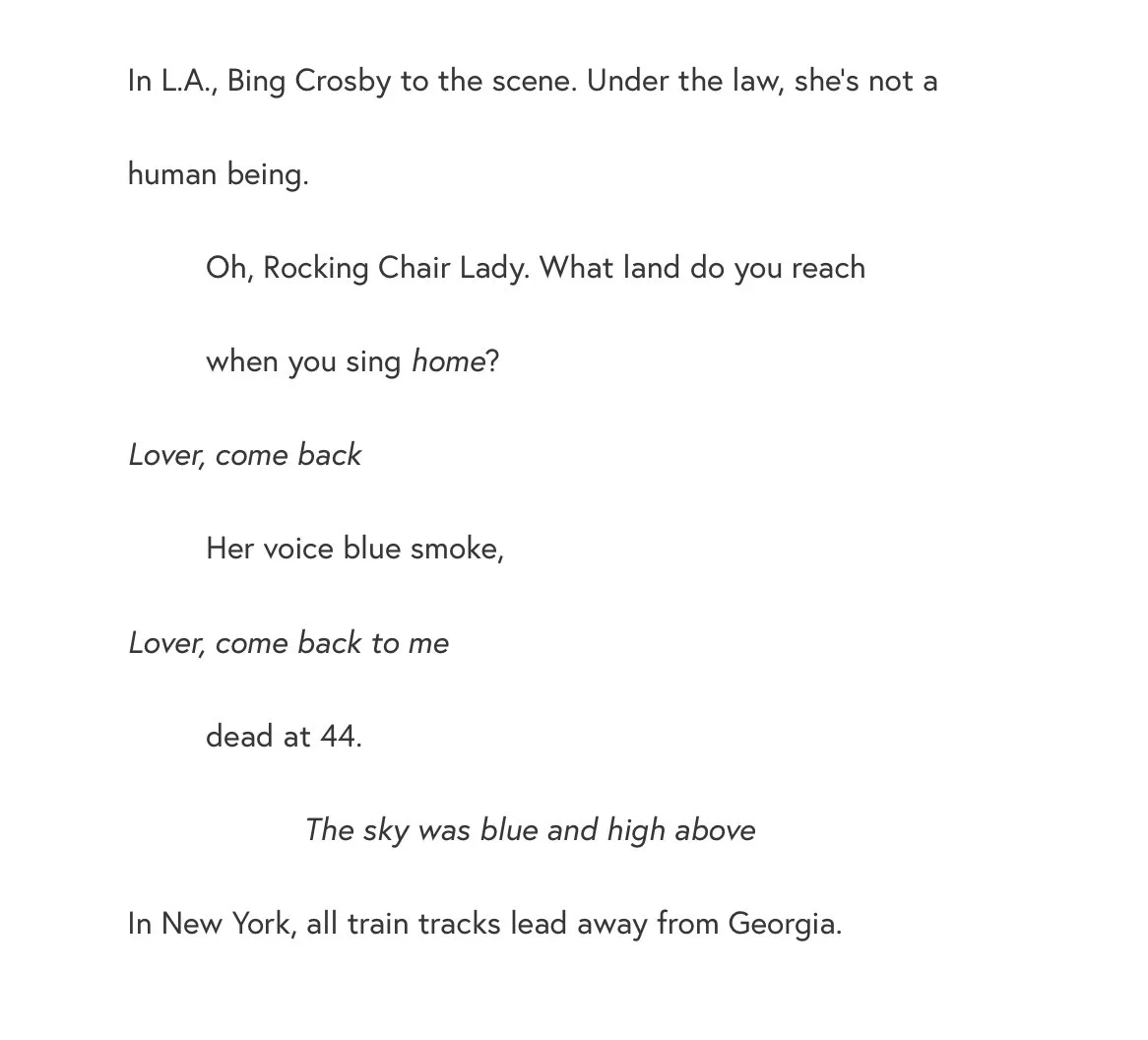

One of my favorite poems in this collection is “FOR MILDRED BAILEY, in three parts”, which centers around Skitswish singer Mildred Bailey, also known as “The Rockin' Chair Lady” and “Mrs. Swing.” In this piece, the collection makes a clear statement about the ability of music to carry memory: “Her angel voice / brings them home / to Cherokee, / the whooping crane. / She lets her sons fumble back.” Mildred Bailey was inducted in the Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame in 1989, but it wasn’t until more recently that the jazz world recognized her Coeur d'Alene ancestry and indigeneity; in fact, in textbooks like The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz she is described as “the first white singer to absorb and master the jazz-flavored phrasing.” Within this three part poem, biographical details about Bailey intertwine with lyrics from jazz standard “Lover, Come Back to Me”:

The Sky Was Once a Dark Blanket considers lineage—familial, musical, poetic—and questions what it means to carry these lineages forward. And yet, the collection still exists outside temporality—even with mentions of Baja Blasts and when the speaker feels “god in this Taco Bell tonight.” Time does not matter here. The sky was a dark blanket before “Coyote threw / up a basket of stars to shatter the black / into brilliance," and the desert was, at one time, an ocean—“sun, plankton, pearl, / blood, ancestor, cloud.” And in this song, we can still see the whales, their mighty tails, dipping below the water, and Mildred Bailey once more sweetens a room with her voice. The speaker tells us “the whole world remembers / what it once was.” And it does. It comes back like a needle on a turntable, singing the whole time. In Drake’s debut collection, remembering is an act of love, and poetry is a place we can access love. Who told the speaker that “The sky was once a dark blanket” in “Creation Story Blues”? Undoubtedly someone she loved. Undoubtedly someone who is part of this song.

Katie Grierson is a poet diligently working on her MFA at Arizona State University. She has been recognized by the Academy of American Poets College Prizes, by the National YoungArts Foundation, as a Best of the Net Nominee, and has had her work supported by The Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing. She hopes to one day become a beam of light.