John Murillo Interviewed by Brandon Blue

JOHN MURILLO is the author of the poetry collections Up Jump the Boogie, finalist for both the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Pen Open Book Award, and Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry, winner of the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and the Poetry Society of Virginia’s North American Book Award, and finalist for the PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award and the NAACP Image Award. His other honors include the Four Quartets Prize from the T.S. Eliot Foundation and the Poetry Society of America, the Lucille Clifton Legacy Award from St. Mary’s College of Maryland, two Pushcart Prizes, two Larry Neal Writers Awards from the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, the J Howard and Barbara MJ Wood Prize from the Poetry Foundation, an NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship, and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, the Bread Loaf Writers Conference, Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, New York Times, Cave Canem, and the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing. Forthcoming publications include Dear Yusef: Essays, Letters, and Poems For and About One Mr. Komunyakaa, coedited with his wife, the poet Nicole Sealey, and forthcoming from Wesleyan University Press; and Concerning the Angels, his translation of Ralphael Alberti’s poems, forthcoming from Four Way Books in spring 2025. Recently, he served as associate professor of English and director of creative writing at Wesleyan University, where he founded with Wesleyan University Press, The Cardinal Poetry Prize, the first ever book prize for poets 40 and over. He is a professor of English and teaches in the MFA program at Hunter College.

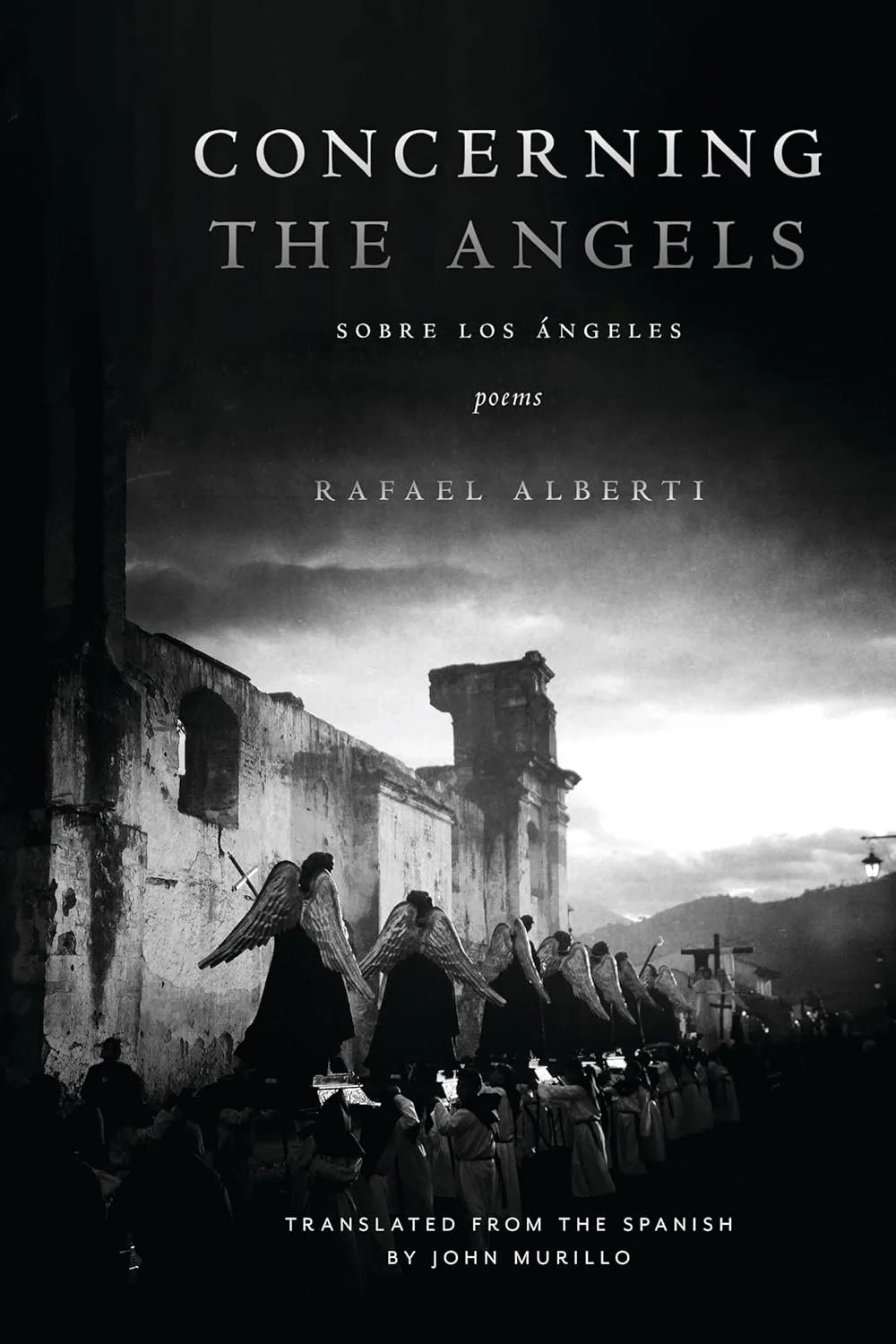

From Translations Editor Brandon Blue: Concerning the Angels (Sobre Los Angeles) poems by Rafael Alberti, Translated by John Murillo (Four Way Books, 2025), brings Alberti’s collection back to an English-reading audience. Despite having been “penned a masterwork of social and psychic malaise as deserving as any of its place in the global canon,” previous translations of Concerning the Angels have fallen out of print and have disappeared into relative obscurity among readers of English language poetry. Murillo’s translation makes an argument for why this magnum opus should never be forgotten again. Murillo ushers a necessary voice that considers existentialism, loss, and the human psyche.

Concerning the Angles (Four Way Books) is available for purchase here.

Photograph by Marcus Jackson

Brandon Blue: Lawrence Venuti says, “the translation or adaptation inscribes its interpretation at every stage in the writing process, starting from the very choice of the source text and including every verbal choice,” and as you write in your introduction to the collection, Concerning the Angels has been translated three times before and has gone out of print. So I’m wondering, why Rafael Alberti now? What about Concerning the Angels feels urgent for your own life and our contemporary moment?

John Murillo: In answering this, my first instinct is to want to use this opportunity to try to say something profound about our current moment, our recent history, and to draw parallels between this political climate and the one that overwhelmed Alberti’s Spain in the 1920s; and maybe say something either about his prescience or about how, because of how history repeats, what we see as prescience is rooted in our misguided sense of history as something always progressing toward some better day… blah blah, fascism, totalitarianism, blah blah, the poet’s duty, blah blah blah. But while some of this may be true, my truth, my reason for translating Alberti now, is much simpler: I find the poems beautiful and deserving of a wider readership. That he has gone out of print—that this particular collection, considered by many to be his magnum opus, has gone out of print—is shameful.

As I write in the introduction, Alberti was a contemporary and close friend of Lorca. And, until Lorca’s assassination in 1936, he and Lorca were often mentioned in tandem, as the two shining lights of “The Silver Age” of Spanish poetry. Many even considered Alberti the superior poet. But unlike Lorca whose life and death have been the subject of elegies, essays, and even a couple mediocre Hollywood films; Lorca who, legend has it, died facing a fascist firing squad—maybe for his politics, maybe for his queerness, probably both—and has therefore become a symbol of sorts; Lorca who died, and now lives, forever young and handsome… there is nothing sexy in Alberti’s biography. Or, let’s say, nothing as sexy. He lived much of his life in exile but lived well into his nineties. He got old. And he wrote poems. But as lovely as these poems may be, that’s not been enough to warrant a steady readership in the U.S. where, even among poets, our tastes lean more or less provincial.

BB: Often, when people talk about the challenge of translation, they talk about retaining what is most alluring and impactful in the original manuscript in a new context. These conversations usually revolve around references and idioms, but in my own translations, I confront this question through ratios of strangeness and clarity. When translating a poem where meter tells us something very specific about the poem's logic, often, image and syntax must accommodate that meter for a new audience to access that original metrical meaning. I have always been told, and believe, that great poems are hard to paraphrase, and yet to retain that mystery of a poem, a translator has to make a decision of how best to recreate that magic, thereby paraphrasing the poem for its new readers. They must decide that the meter is the magic of the poem in the aforementioned hypothetical. Where did you land on the mystery of any poetic text, and the clarity required to translate mystery?

JM: What we call “mystery”—and I’m assuming, by this, that we mean something like the unknown or unknowable quality in or of a poem—raises the same questions for me as when I hear anyone talk about Duende. Namely, where does it reside? Is it in the work itself? In the eye of the reader? Is it possible for a particular work to be mysterious to one reader and crystal clear to another? The same way a song can leave one listener cold while moving another to rage? As a translator, I try not to burden myself with such concerns as they are largely beyond my control. Or maybe they aren’t. But saying so makes my job a lot easier.

BB: A more concrete way of looking at that challenge is thinking about punctuation, syntax, voice, and tone. As I was reading through the manuscript, although I do not read Spanish fluently, I noted that punctuation, line breaks, and end words were very consistent across texts (a difficult feat!). Like I noted earlier, I agree with Lawrence Venuti when he writes, “translation performs an interpretation, it can never be literal, only figurative, or more precisely inscriptive of effects that work only in the translating language and culture.” I’m curious about your experience of Concerning the Angels, how you experienced its coloring and pace and how that came to your formal decisions? Did you look up any videos of Alberti reading?

JM: I did not. I’m tempted to say, on the one hand, that it might have been useful, that it might have given me some insight into Alberti’s intended rhythms, his cadences and pacing. But as we know, a performance of a text can vary from night to night. Better to concern myself with what’s at hand, which is to say the text itself.

But your question reminds me of an experience I had that changed how I think of reading, but now I understand as relevant to the translator’s work. I took a workshop a couple decades back with the poet Patrick Rosal where he recited an Octavio Paz poem for the class. One participant—this crotchety older white guy who was only there because another workshop he’d paid for got canceled—complained that Patrick’s recitation of Paz was too loud, that when he (the complainer) read the poem it felt quieter, more subdued. Patrick, of course, suggested that there are many ways to read a poem, and that when he read a poem he liked to make it his own. “Well,” said the guy, “that’s all fine and good, but the fact remains: it’s not your poem, it’s his!” Setting aside the possibility that Paz intended his poem to be sung, bellowed even, and that a quiet reading was actually the wrong one, aren’t we always, when reading poems, making them our own? Your Berryman, your Bishop, your Baraka are all very different from mine. And I’m quite sure that Alberti’s Alberti is different from my Alberti.

As for formal and other decisions, I worked intuitively for the most part and, from poem to poem, changed strategies frequently. To the extent that any theories or principles were involved at all, they didn’t guide the work so much as they were discovered along the way or in hindsight. Some of which have already been abandoned.

BB: Translation is often called the closest form of reading. It takes a lot of time to sit with the words, thoughts, logical leaps, and associations of another writer. Some people look at this time as a time “away” from their own work to really work within the confines of someone else’s. I’m a little skeptical about this because I don’t believe there are translations where the translator’s sensibility and inner lexicon aren’t driving the translation of the work. There is no time “away” even when working inside someone else’s language. Have you noticed as you completed the translation and returned to your own poems, any of Concerning the Angels’ logic showing up in your own writing? Any poetic tools, images, or syntax now a part of your poetic toolbox?

JM: I hope that’s the case but it’s too early to tell. In fact, I was going to mention this when responding to your first question: Why Alberti, why now? I wanted to spend time with the poems, I wanted to make them available to new readers, but more than anything, I wanted to steal from Alberti. That is to say, I was hoping that in immersing myself so completely in the voice, syntax, and imagery of a writer of Alberti’s caliber, to say nothing of one so removed from our current epoch, that I would emerge from that experience somehow transformed, that a bit of his magic would make its way into my work. His strangeness, his mysteriousness, his particular brand of duende. I’ve not written many new poems since completing this project, so haven’t had much opportunity to determine whether I’ve succeeded. But I have my fingers crossed.

BB: In the final poem of the collection, “EL ÁNGEL SUPERVIVIENTE” or “THE SURVIVING ANGEL,” you translate, “The snow brought drops of sealing wax, molten lead…All the angels lost their lives./ Except one, wounded, its wings clipped,” which I can’t help but think of as analogous to translation: the new incarnation of a poem as a kind of surviving object of what could have been forgotten. I’m eager to know what you hope will survive and be reinvigorated by this translation of Rafael Alberti through your eyes?

JM: Above all, Alberti’s name. My hope is that even if a reader finds my translation wanting, they are at least intrigued enough to seek out his other work—preferably in the original language—and find something to love. Beyond Alberti, I hope this project will lead curious readers, poets, translators, to ask what other voices we have neglected, to search for them, and to remedy that neglect.

This interview was conducted over email in January 2025

Brandon Blue is a black, queer poet, translator, educator and MFA candidate at Arizona State University from the D(M)V. Their work is featured in the Capital Pride Poem-a-Day event and has received support from the Virginia G Piper Center for Creative Writing and Aspen Words Conference. His chapbook, Snap.Shot, has been published by Finishing Line Press and was named in Poetry Mutual’s Best Books of 2023.