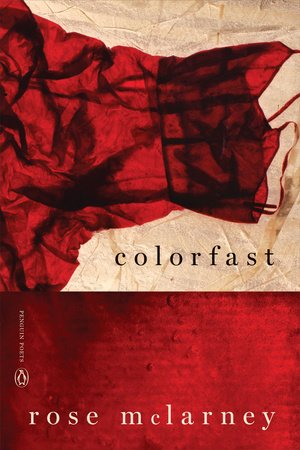

Ella Sexton Reviews Colorfast by Rose McLarney

Rose McLarney’s collections of poems are Colorfast, Forage, and Its Day Being Gone, from Penguin Poets, as well as The Always Broken Plates of Mountains, published by Four Way Books. She is coeditor of A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia, from University of Georgia Press, and the journal Southern Humanities Review. Rose has been awarded fellowships by MacDowell and Bread Loaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences; served as Dartmouth Poet in Residence at the Frost Place; and is winner of the National Poetry Series, the Chaffin Award for Achievement in Appalachian Writing, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers’ New Writing Award for Poetry, among other prizes. Her work has appeared in publications including American Poetry Review, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, New England Review, Prairie Schooner, Orion, and The Oxford American. Currently, she is professor of creative writing at Auburn University.

Colorfast (Penguin Poets) is available for purchase here.

Rose McLarney’s collection Colorfast is a staggering pondering of girlhood, southern identity, and the hauntings of history. Out of nature and out of food, McLarney extracts carefully crafted observations about what it means to be a woman, particularly a Southern one. From blackberries to nutmeg to the keeping of recipes, these poems consider the traditions, cultures, habits, and traumas that make their way down through generations.

Colorfast is fittingly built around two long poems, “Receipts” and “Cakewalk,” each concerning the book’s throughline of food as it relates to womanhood. “Receipts,” the first long poem, draws evocative lines between Mary Maddison, a 17th-century girl who is known for leaving behind practiced signatures of her name, and modern schoolgirls learning to write.

The kitchen is where girls

in the 1600s, in England, learned.

From listening to talking women, watching

the math of measuring, and copying

receipts, recipes.

Mary’s manuscript was the margins

of a cookbook--the paper available to her.

By pinpointing this domestic space—the kitchen and food—as Mary Maddison’s backdrop, McLarney weaves a nuanced tale within gender’s ever-lurking presence. Her poems brim with wit about the strength and prowess that cooking requires, and therefore the irony of cooking being considered inferior, weak, women’s work; considering “the imperatives in recipes”, McLarney questions,

Pound, peel, slice,

scald, stir, skewer;

Is a cook not given examples

of how to speak commands?

This humor and understanding is balanced with the struggle of girlhood, the historical oppression of misogyny and the knowledge that so much of life for women can be painful. The end of “Receipts” returns to Mary; the narrator once again considers the relation between Mary Maddison and her own journey learning to write. She wonders,

Did Mary ever have a chance to offer

directions written in her own hand

to a friend, ever have enough free paper?

Perhaps I should have taken pride

in my wild childhood Ys and Ts,

that shot out extra branches,

like trees.

The narrator of this poem expresses with aching subtlety the wish that Mary had the same freedom that she did—while still understanding that, in many ways, her own freedom was lacking (this detail is emphasized in the very first lines of the poem, in which the narrator reflects on always trying out new last names for herself, bracing for the inevitable loss of her own). It is this nuance and allowance for ambiguity in the female experience, which is such a vast and varied landscape, that allows McLarney’s works to shine.

The recurring imagery of food and cooking not only becomes a vehicle for femme identity, but also identity as an Appalachian and a southerner. “Cakewalk” examines a southern community through the different desserts brought to the titular school event, holding a critical lens up to poverty and perception, especially through the eyes of children. The narrator of the poem is unable to help considering the origins of the tradition, reflecting,

What I did not learn until twenty years after,

but is known for sure,

is that cakewalks come from plantations,

were performances slaves were forced

to put on, parading in front of their masters.

So how is it cakewalks were held at my school

and children were brought to them, happily?

The presence of history looms over all of Colorfast, and it is not a pretty one. The South’s racist and misogynistic past, so often ignored in works that center nostalgia, is reckoned with in “Cakewalk” and all of Colorfast’s poems head-on. The pieces expertly walk the delicate line between retraumatizing and providing catharsis for the reader.

In this way, McLarney’s observations about southern life are relentless in their criticism, but still they remain kind; they strive for a future that will hold space for everyone. Poems such as “Fossils Aren’t Found In Appalachia” and “In the Gem Mine Capital of the World” examine the wider scope of Rust Belt life, a forgotten community in all its ugliness and beauty, with a searing and yet quiet vividness; and poems on a smaller scale are no less arresting. The poem “Nutmeg and Mace” meditates on motherhood and the grief it causes both mother and daughter. Cinnamon toast made before school is compared to the cinnamon used in Ancient Egypt for embalming; a weapon traditionally wielded by women against assault is compared with a spice used in baking, with the lines

Nutmeg is made of the durable seed

of Myristica fragrans, mace from lacy red

fibers in the surrounding flesh.

Mace is worth more

In McLarney’s collection, girlhood is not all sweetness, but crucially, it is not all suffering, either. Girlhood is mace and nutmeg both; it is resilience and burning and pocket-sized liquid ammunition, and it is also joy and love and family recipes passed down. There is grief inherent in the places where women have been trapped throughout history, but Colorfast emphasizes the flowers that grow between the cracks. Anywhere women have been confined—such as the kitchen—women have built their own language.

Much like “Receipts,” the narrator of “Nutmeg and Mace” extends her consideration into history, but not so far back as the 17th century; she ponders her own mother, and the person that she’s had to become because of the world’s expectations for her. What this poem, and every other poem in this collection understands, is this: being a mother, a daughter, an American, a southerner, a miner or a nutmeg plant, means a constant fight between what to let go of and what to cling to.

Ella Sexton is an undergraduate literature student at ASU who has lived in Phoenix, Arizona, all her life. Her aspirations include graduate school, teaching, and authoring, and she is always surrounded by writing works in progress. Outside the classroom she enjoys reading, painting, searching for strange trinkets at thrift stores, and spending time with her cat.