Kristen Therese Chua interviews Lauren Davis

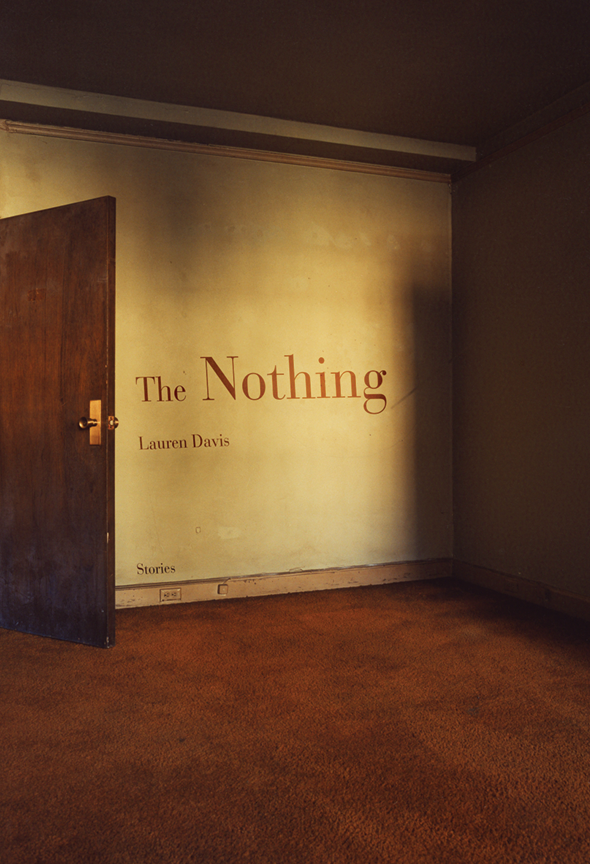

Lauren Davis is the author of the short story collection The Nothing (YesYes Books), the poetry collection Home Beneath the Church (Fernwood Press), the Eric Hoffer Grand Prize short-listed When I Drowned (Kelsay Books), and the chapbooks Each Wild Thing’s Consent (Poetry Wolf Press), The Missing Ones (Winter Texts), and Sivvy (Whittle Micro-Press). She holds an MFA from the Bennington College Writing Seminars. She is a former Editor in Residence at The Puritan’s Town Crier, and she is the winner of the Landing Zone Magazine’s Flash Fiction Contest. Her stories, essays, poetry, interviews, and reviews have appeared in numerous literary publications and anthologies including Prairie Schooner, Spillway, Poet Lore, Ibbetson Street, Ninth Letter, and elsewhere. Davis lives with her husband and two black cats on the Olympic Peninsula.

The Nothing can be purchased on YesYes Books’ website here.

From Editorial Assistant Kristen Therese Chua: In Lauren Davis’s debut fiction collection, The Nothing, Davis takes readers through nineteen short stories, each one just as much surreal and dreamlike as they are grounded in reality. In a world in which ghosts are commonplace, readers will find themselves not only haunted by these apparitions but by the very human characters who inhabit the narratives. Dark and earnest, Davis’s collection explores themes of love, grief, isolation, and connection.

Kristen Chua: The stories in The Nothing touch on a number of themes but, at the heart of each one, I found characters with a deep need to understand as well as to be understood. One of my favorite lines from your collection comes from “Please Enjoy Going Where You Are Going” that reads: “A secret can hide anywhere in the body, and his secret lived in her throat. She could feel it catch when she neared him.” I found your examinations of interpersonal relationships between characters to be especially compelling in contrast to the theme of isolation present. Can you speak more on this relationship between connection and isolation conveyed in your work?

Lauren Davis: Thank you for this question. For years, I identified as a poet. Though I had written fiction in academic settings, I did not write fiction outside of those classrooms. And the poetry I wrote tended to always have a confessional leaning. I wrote about relationships, which oftentimes meant writing about grief and loneliness. After my first full-length poetry book came out, I turned more to persona poetry, and I was further able to explore those themes. Still, once I started writing short stories, I realized fiction was allowing me to say things I had never been able to say in poetry. I was exploring isolation and its implications in a way that had not been available to me before. I had been writing about connection and isolation previously, sure. But I had not been writing about the consequences of isolation, not in the way these characters’ experience their emotional landscapes. This book became a way to honor the costs of loss.

KC: I was struck by how much this collection reminded me of The Haunting of Hill House and recalled the blurb I read, which mentions the Shirley Jackson-esque nature of your characters. I also felt as though your prose at times held a folktale or fable-like quality to it, particularly in “Gekker” and “The Sleeping Cure.” I was curious as to where you draw your inspiration from. Additionally, have there been any non-literary works that influenced your work?

LD: I grew up with fairytales, but only the Disney whitewashed versions. I therefore had no interest in them until I came across The Turnip Princess. The stories aren’t edited. They are instead recorded from oral storytellers. The rough edges of the narration are not smoothed out. They’re dark and unnerving and often made me laugh out loud. I was immediately enamored. After that, I could not get enough of fairytales, and thus began a love affair with a new genre. It was then inevitable that a dancing cat or a talking moon would find its way into my work.

KC: Though each story is tied in some way to the collection’s title, I noted “No Eyes for Them” as the most significant tie to The Nothing as we follow a character who is aware of and explicitly acknowledges “the nothing” she speaks to when she speaks to the men and boys she is unable to see. What was your intent behind this story in relation to the title? Did it serve as its basis? Or, rather, did you find that it is the title that informed the story(s)?

LD: The title of the book came much later. In fact, for the longest time, the title was The Milk of Dead Mothers. The publication announcement used that title, and I held onto it for a very long time after. During the first round of edits, my publisher mentioned changing it, and my hackles immediately went up. I had already told everyone it was Dead Mothers! She mentioned it during another editing session, and the wisdom of this finally started to creep in. But it wasn’t until I found myself avoiding telling people the old title that I realized how wrong it was for the book. If I couldn’t say it out loud, for whatever reason, how was I possibly going to hold onto it? So I went through the book looking for phrases that jumped out at me, very similarly to how I treated finding a title for my poetry collections. Finally, I realized that the word “nothing” was used repeatedly throughout the manuscript. It was like an incantation. It was everywhere. It was the thread that held the book together.

KC: Alongside the shadows and other unexplained forces at work, I noticed there are a number of ghosts or ghostly figures that haunt the narratives. What role do these various forms of hauntings play in this collection?

LD: Let’s just say I was afraid of the dark for longer than is developmentally the norm. And I’ve been told, again and again, write what you are most afraid of. So here we are.

KC: I noticed the mention of the town Sloan as well as the location of Mud Lake in more than one story and was intrigued by the connections woven between them, despite them all remaining standalone. I also loved the tie-back to the final story provides when it comes to this connection. Would you say each story exists within the same universe? What led you to their collective throughline?

LD: For the most part, yes, the stories are in the same universe, though I like to think there’s a bit of overlap of parallel universes at play. The idea of the collective throughline actually came from the poet and editor Denton Loving. He read an earlier version of the manuscript and mentioned adding what he called “connective tissue.” His advice was vital. These stories, especially considering how much I play with different genres, very badly needed something to tie them together, lest they float off and get tangled in the trees. He gave me that.

KC: Having previously published poetry books and with this being your debut fiction collection, I wanted to ask a craft question. When writing a short story, how does your approach to the process differ as opposed to when you are writing a poem? How and in what ways might the process be similar for you?

LD: The process is similar in that I try to let go and let the piece guide me. I try to be its conduit and not its master. Which means that the initial creation process looks essentially the same. The editing process, though, is a bit different. With poetry, I am concerned with the craft elements, with emotional (not factual) honesty, and with clarity, whatever that may mean given the piece in question. Prose, though, feels like a different animal during the editing process. It feels like it demands a different, or additional, type of precision. Does the room my character inhabits make sense in space? Would the character really travel up those stairs that quickly? Oh dear, I forgot she’s in heels. She would probably take those off beforehand. Paying attention to the corporeality of spaces and multiple characters feels like a different muscle than what I often have to exercise in poetry.

KC: Of all the short stories in the collection, which was your favorite to write? Is there one you find you resonate with the most? Why?

LD: “The Sleeping Cure” was my favorite to write, for sure. It demanded very uncomfortable research. And then, for the longest time, I could not make the piece work. Something was quite wrong with it. I brought it up to my husband multiple times, and then finally he asked me a simple question about one of the characters. What if, instead of this way, they were this other way? Sometimes we really do need the people around us to show us a truth about our work. As soon as he asked the question, everything fell into place. The struggle stopped, and the story found its legs. The story doesn’t necessarily personally resonate with me that much. I think there are scraps of myself in each story, little crumbs of my real self, though.

KC: What does The Nothing mean to you? And, for anyone who may pick up this collection, what do you hope they will take away from it?

LD: For me, The Nothing is a way to honor grief in its many forms, mine and those of others. I hope readers may recognize their own humanity in these characters’ struggles. We are not all that different from each other, especially when our faces are reflected in the surface of a funhouse mirror.

Editorial Assistant Kristen Therese Chua is a graduate of Oklahoma City University where she received her BFA in Acting and minored in Psychology and English. Kristen recently second bachelor’s in English, Narrative Studies at ASU