Unhinging and Unspooling: Allegra Hyde Interviews Lisa Locascio

Lisa Locascio’s writing has appeared in n+1, Santa Monica Review, Tin House Flash Fridays, Bookforum, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and many other magazines. She is the first Anglophone writerto be granted an interview by Carolina López, widow of the Chilean author Roberto Bolaño, the text of which appeared in The Believer in June 2014. A recipient of awards and honors for her writing including the Virginia C. Middleton Fellowship, the 2011 John Steinbeck Prize for Fiction, the 2014 Dr. Fred Robbins Memorial Award for Emerging Writers, the Dorys Grover Award from the Western Literature Association, and residencies at Djerassi, Virginia Center for the Arts, and Prairie Center of the Arts, Lisa lives in Los Angeles, where she teaches at the University of Southern California and in the MFA program at Mount Saint Mary’s University.

For more from Lisa, check out here Issue 56 Contributor Spotlight here.

From Former Prose Editor Allegra Hyde: While finishing my term as prose editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review, I had the chance to work on our literary darling: the “Chaos Issue.” Gathering material for this issue granted the opportunity to engage with writers exploring the far-reaches of form and content, among them Lisa Locasio. Though her contribution to the issue, “Lab,” runs fewer than two pages, it presents readers with a starkly uncomfortable, yet eerily engrossing situation, the jarring honesty of which is hard to shake. Locascio and I spoke over Skype in March.

It seems like you have your hand in a lot of (literary) pies. You’re an editor, you’re teaching, you’re writing fiction and also heavy-hitting critical prose. I was wondering if there was an area with which you most identify, or assume as your primary identity.

Lisa Locascio: That’s a great question because it’s actually one I’ve been thinking about a lot. The identity I calibrate everything around is fiction writer, but I think that has become more complicated the longer that I’ve been doing this. When I started out—and I tend to think this is different from other people, but maybe it’s not—I started writing young and was praised for doing it. When I was in high school I was involved in a creative writing workshop that met in Chicago, and it really wasn’t for students like me—it was for what are euphemistically called “at-risk urban youth”—and it ended up being the best experience of my young life. I grew up in a really diverse, liberal suburb, but it was definitely an affluent one. Writing was always about exploration, meeting people who were really different from me, hearing their stories. Until college, though, I self-identified as a poet, not as a fiction writer. All of my pre-college success—such that it was—was in the realm of poetry, but when I was in college I made this concrete jump to fiction. This might sound naïve, but I thought: “Oh, maybe I’ll reach more readers if I write fiction” [laughs].

I chose my undergrad program, the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at NYU, because I knew I didn’t want to be an English major or a history major. My interest lay in the interstices of culture and society and literature. At Gallatin I was able to make an argument for a weird central path that was literature-focused, but with a lot of creative writing coursework and a lot of analysis of films and myths and other things. Going into a PhD after the MFA (Locascio also completed her MFA in Fiction at NYU—Ed.), however, it became clear that I wasn’t someone who had an undergraduate English degree. I never had to take the big survey courses, so there are these hilarious gaps in my canonical reading. And the undergraduate professors who I was drawn to were specialists of pre-modern non-western fields. So I came out with a pseudo-specialization in Indian and Japanese lit, because I liked working with those people. All of this really informed my fiction—and later my criticism, which was born wholly within my PhD. I see it all as arms of the same body, the same project. For me the really rewarding thing is the idea that there’s this voice that’s being honed and shaped and that it expresses itself in different venues.

Having been on the job market recently—one of the jobs I was in the running for was a creative non-fiction job—I actually felt some of the difficulties of these identities that I see as really fluid and hybrid and feeding into one another. Suddenly they became really distinct. Partially because there’s an imbalance in the amount of fiction I’ve produced versus the amount of creative nonfiction, but also I realized because there are people writing exclusively nonfiction, as exclusively as poetry and fiction are kept separate. Although I don’t write much poetry any more, to me there’s still an associative and continuous connection. The way in is always the creep or the voyeur—that’s the identity that I connect with—and that’s where my fiction and ultimately all my writing comes from.

AH: I like the idea of it all being arms of the same body. And it makes sense, right, that it would all be part of the same preoccupation with the same thing. We’re just looking at from different angles.

LL: I think I started pushing against boundaries in a more conscious way when I started my PhD, because my program has a creative side of the department and a critical side of the department. And early on there was a lot of tension between the two cohorts. It manifested as a theory camp and a creative camp. I really struggled with that. I fought against it because I was really tired of being prescribed theory as an answer to how to read. I also felt insecure and like I didn’t know what I was doing. Now realize that so much early theoretical training is just everybody faking their way through it.

And then in the third and fourth year of my PhD I started doing residencies and found myself around these other writers and artists across the spectrum who hated academia. I came into these residency environments thinking I was this firebrand with a foot out the ivory tower: maybe I’d be an academic, maybe not. Yet I was meeting people who became visibly upset talking about critical theory and academic programs. I found myself defending it—and I was like what the fuck is going on? How am I defending these things that are driving me nuts and making me feel anxious for years? And I think that’s kind of where the interdisciplinary focus came from. As much as I had been resisting elements of the PhD program, it had been changing me the whole time. I found the work meaningful! I think there are people who go through creative PhDs who have a minimal engagement with the critical work, but I was never going to do that.

Part of the multifaceted nature of my body of work came from the practical fact that I will apply for any funding opportunity if there is any way I can make it work. A lot of my research on Bolaño and the fire behind that came from the fact that I happened to be funded through this Spanish research fund, even though I don’t even read and speak Spanish.

There were a lot of moments during my PhD where I did have the benefit of being totally alone. I had a fellowship year. No one was leaning on me for anything. But it could get—though it’s not always like this—it could get really depressive and lonely, especially with a novel project. The isolation of being a writer is one of the difficult things for me because I love being around people, and that’s why I like teaching. So it was kind of an approach that developed from an understanding of what helps me in my work and also helps me feel human and calm.

AH: Speaking of the Bolaño project, I was wondering how that critical study has influenced your creative work.

LL: The core of the Bolaño project—or the seed if you want to call it that—is that I am an inveterate fan. I don’t know really how to interact with human beings, or media, outside of obsession [laughs]. That sounds really extreme, and I don’t mean it in a scary way, but that’s just kind of how I move through the world. And think that’s partially because my parents are fans, canonical collectors and into stuff like that. It’s also just who I am. I think a lot of my writing career has been about accepting that about myself, that I am a categorical obsessive. So I say that to preface the fact that for a long time I was just a big Bolaño fan. But I kind of have this strange habit with artists that I admire. I’ll be aware of them and seek out everything they produce for a long time before everything really clicks into this arch obsessive mode. The artist who did that for me before was David Lynch, who is someone I had grown up around and was actually really frightened of, and I wouldn’t watch his movies because they scared me too much. And I remember when I was twenty, my parents and I were in York, England, on our way to Scotland because I was studying abroad there, and I was reading a book about Lynch and it clicked into my head: you’ve been scared of him forever and that’s because he’s a powerful artist! And that opened up five years of obsession with David Lynch.

Honestly, something kind of similar happened with Bolaño. Because at the time when Bolaño really arrived in the American literary market, I lived in New York and worked at Farrar, Straus & Giroux, which was the publisher of his bigger books, so I was really aware of him. Then I started reading him for the coursework of my MFA and I liked him, but even though I was really into his writing, it wasn’t set apart for me. As I left New York and moved to California, however, I continued having these really meaningful experiences with Bolaño’s books. In 2012, I got an email from my administrator saying that there’s this fund for projects that connect California to Spain, either industrially or culturally. I thought this was the most ludicrous description. Because how could a state be connected to a nation? Spain is a really capacious place. But I applied for it and I got the money. That’s what led me on the whole trip that ultimately led me to interview Bolaño’s widow a year later. It was unlike anything I’d ever done because it was definitely more of a journalistic project. I liked being around people and I love to travel. The sort of ballsiness of going to a place and really having my primary research strategy being walking into a place and asking in broken Spanish if someone remembered or knew Roberto Bolaño didn’t seem right—I’m kind of a planner—but the enormous thing that I learned from the experience was that there’s a lot of meaning in what I connect to.

I hate to say that because my students are always talking about connection. They say, “Oh I didn’t connect to that,” and I’m like, “It doesn’t matter, it really doesn’t matter if you didn’t connect to it,” because what matters is exposure, and that’s an educator’s first job, to expose. But, at the same time, connection is important, of course. And I felt like the project enabled me to discover something about someone who I felt really intimate with, an intimacy to which I didn’t think I had the right. And I still don’t know if I do, but the Bolaño experiencet was very beautiful—I’ll even say spiritual and mystical—on top of all the artistic dividends, because I couldn’t figure out how I got the opportunity that I did. I mean, I understand that I did an enormous amount of work to make it happen, but still: how did I go from being an admiring reader of Bolaño to the first English-speaking writer his widow Carolina López would speak with? The very cheesy, yet very true thing I can say about it is that it taught me a lot about the power of writing, and how an artistic conviction and a creative vision for your life can—I’m not going to say pan out, or make you really happy, because Bolaño’s great success didn’t come until after his untimely death—but that it’s meaningful and that a path in itself. And even though I’ve had a really privileged passage through academia, and no one in my family ever said, “Don’t do this,” or asked “What’s wrong with you?” or anything like that, it’s very easy to lose faith in this bizarre thing that we do.

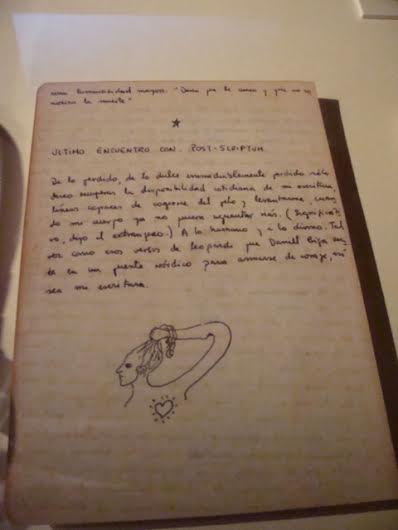

So, that’s why I have my Bolaño tattoo. It’s a drawing he did on a manuscript on the last page of Antwerp. It was a very cinematic and emotional experience to see these pages he had handwritten, which were part of the first public exhibition of his work, at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona in 2013. I chose this image because he’s writing about how it’s almost like a prayer. Bolaño writes:

Of what is lost, irretrievably lost, all I wish to recover is the daily availability of my writing, lines capable of grasping me by the hair and lifting me up when I'm at the end of my strength. (Significant, said the foreigner.) Odes to the human and the divine. Let my writing be like the verses of Leopardi that Daniel Biga recited on a Nordic bridge to gird himself with courage.

That resonated with me so beautifully. I’ve tried to run away from writing so many times. I’ve always wished that I was a writer-dentist. You know, someone who has a day job that’s lucrative and enjoyable and maybe not passionate—but still something that I could go do and then be like, “I did that thing and now it’s over and now I’m going to write.” But every time I’ve tried to make that happen it’s been a hilarious disaster. Not in that I have been unsuccessful outside of my field, or outside of academia, but those forays have really cut into my writing time, and even my ability to write. I never wanted to be a teacher because I didn’t think I could live up to my teachers, who have always been my heroes, seemingly superhuman in their powers of communication and illumination. But teaching has become an amazingly generative component of my creative process, which was a wonderful discovery I made in my MFA, the first time I taught at the university level. So this is what it is. Who I am. And I think there’s a certain embracive oblivion in that. But not a negative oblivion, it’s allowing things to flow and take their path.

AH: Speaking of handwritten pages, do you write by hand, or are you a typist?

LL: I am primarily a typist. But in certain periods I keep a notebook. I’ve had one now for a while, since June or July of last year. It’s interesting because I don’t really think there’s any conscious rhyme or reason for when I have one and when I don’t. But I’ve kept enough of them. When I started out writing poetry and thinking of myself as a poet at fourteen, a notebook was all-important. If I lost my notebook it was like a huge deal. I mean it would still be a huge deal if I lost my notebook. One thing is I’m a lefty, and though my dad spent years holding my hand as I wrote to try to teach me the proper grip, I do get significant cramps if I write everything out. I think that’s part of why I moved over to the computer pretty quickly. When I used to write poems in my notebook, part of my revision was typing them up. That was then first round, and I’d go from there. With fiction it’s just much easier to produce it in Microsoft Word. Whenever people talk about how outmoded Word is I get really defensive and think, “Don’t take Word away!” Because I like that it’s a physical page. People point out—and they’re not wrong—a lot of what is produced in Word is never going to be printed out, so why are we still working on an 8-by-11 page? That just makes me bottomlessly sad, because the visualization is really important to me.

My notebook runs from being something as personal and intimate as a diary, but I’ve found that I can only really have one notebook at a time, so it’s also where I’m going to take notes at a faculty meeting. It’s kind of a weird document. Sometimes now and then I’ll really get going on something and write fiction by hand, but proportionally it’s never really the whole story. I would be interested to try.

AH: So do you think the hodgepodge notebook, which might have faculty meeting notes and maybe bits of a story, relates to the way you are working in so many modes—your multi-armed approach?

LL: I never thought about that, but I think that’s absolutely right. What has illustrated this for me is the scholarly work I’m doing for my PhD, which has been very difficult because I have a lot of critical and scholarly projects that can’t be my dissertation for reasons of discipline and scope. Coming up with a rationale for why I want to write about these books in the actual critical dissertation project was really hard. After I killed myself writing this forty page prospectus, I had this idea come to me—I don’t know how to make this not sound goofy as hell—but I had this idea come to me in a dream state that pulled the whole thing together, and really collapsed the last boundary. I was already okay with fiction and creative nonfiction and poetry being the same thing, but when I realized that that weird intuitive force was really important to listen to in terms of scholarship that was really freeing—but also really scary. It would be scarier if I was just a scholar, if I didn’t have the creative profile to fall on, people would be like, What the fuck are you doing? I really admire books like White Girls by Hilton Als, which is this incredible cultural criticism that is totally personally inflected. I just think that’s the meaningful mode of inquiry, and that if you pretend there’s a boundary between them then you’re ignoring something important that could help you and could probably, more importantly, could help someone who might read it.

And the other thing I might say about the Bolaño thing is that I just get these lovely letters from men who have read the Bolaño stuff and they want to ask me questions, or “to correspond,” and they all write like Bolaño. They’re like, “And then I got on a bus, and there was a stray”—and I’m like, “You know you don’t have to write like Bolaño.” But I think it’s beautiful, this beautiful performance of enthusiasm and connection. I never quite know how to write back. That’s part of it too. I don’t think the intersection ever actually ends.

AH: It’s interested that all the people who have responded have been men. I’m wondering about the tradition of machismo in Bolaño’s work and how that relates to your interests, because when I think about your writing there’s so much emphasis on female sexuality or these female experiences that seem, in some ways, contradictory to the Bolaño mode.

LL: I totally understand that Bolaño’s work is riddled with machismo, but I never see it when I read it. I only ever see him as terribly, terribly tender, and it’s interesting, because another writer who people sometimes mention in the same sentence with Bolaño, who I never had any use for, is Charles Bukowski. I just wouldn’t read a single fucking thing by Bukowski. I just remember some poet friend of mine saying when I was in college, “You know what’s so frustrating about Bukowski is that you go to a bookstore and they’ve got one shelf of poetry and all of it is Bukowski except for like two books.” And it’s true. And the cult of Bukowski is so hyper-masculine. But then I did finally read Bukowski, Post Office, and later, Ham On Rye, and even though that aggressive machismo can be his forward thrust, there’s a lot of other things going on behind it. A great tenderness of a completely different variety. Those scenes in Post Office where he’s just weeping and drinking in bed, so exhausted by his horrible job—it’s difficult to see him as an agent of the patriarchy. He’s just another victim of capitalism, and a tenderhearted one with a good ear, at that. So I guess I would say that in Bolaño it’s similarly complicated, even if I personally rarely find myself reacting to or even noticing much machismo in his writing. The sexual self in Bolaño is deeply vulnerable and very very fraught and prone and abject, and his characters defy categories when they enter the bedroom.

In the first year of my PhD, which was 2010, I was really frustrated. My first book wasn’t going to get published. It was about the interior lives of young girls, and I was pretty sure—I’m still pretty sure—if it was about the interior lives of young boys it might have gotten published. I’m just going to put that out there. So I was in this dark place and I thought, okay, I’m going to write a story that’s going to give people what they want. And I just did my best Bolaño impression, honestly, although I didn’t feel cynical about him or the story. I love the story, which is called “Love Story” and appeared in Reed Magazine out of San Jose State in 2011. It was a very deeply felt story but also kind of a joke to make myself feel better, because we’ve got this unnamed male protagonist, sexy ladies, a bar, strippers and prostitutes, vaguely apocalyptic vibe, and the story won this huge prize! [laughs]

Like I said, I don’t feel cynical about the story, and it also touched me because the judge was Daniel Alarcón, who is kind of a descendant of Bolaño. It felt really validating. And obviously it’s nice to win a prize, but it also made me think about what’s going on with perspective in my stories and wonder if there was a way I could take this style that I love in one person’s work and combine it with other kinds of work that are more sort of classically female-oriented?

I wanted to blow up that staging area. That is what sex and intimacy is to me: a parapet that you can walk on and look down upon yourself from. And that was just really, really interesting. I mean, I have some very strong opinions about some Bolaño gossipy things. Like I find Isabel Allende’s crusade against him really really funny because I think she’s just the biggest peddler of giving Americans and Europeans what they want about South American—and South Americans what they want about South Americans. Bolaño believed that magical realism was an epochal failure because it encouraged readers and South Americans to look away from the enormous death and destruction of the Seventies and instead at a sublimated expression of something beautiful and appealing. And I’m nowhere near as much as a hardliner or an expert on it as he was, but I kind of feel the same way. Witness is very important, as much as I love magical realism and probably employ a weird version of it in some of my work. I think Bolaño was true to his own subjectivity and that was a macho one, but I don’t have a problem with it being a macho one if I can be my own version—it feels like a female machismo. An openness. With Bolaño I feel like he’s open more than he’s macho. But it’s totally a valid critique of him.

Another thing about me that makes me kind of a weird scholar-critic, is that I do have favorites for whom I forgive things. I think there are some texts that are so intrinsically gendered and classed and raced that we can’t teach them without considering where they come from and can’t endorse them to our students without some caveats. It’s a problem I face every time I teach Joan Didion. I’m gaga for Didion. I think she’s just a crazy genius, but to a roomful of students who are not white and who do not come from privilege, Didion is kind of a hard sell. How do you justify this arch, cynical, detached, incredibly artistic and subjective take on cultural criticism? I don’t have the answer. I’m just interested in the conversation. I think with most singular artists you find that problem. Because if they’re singular enough to be thought of as a singular artist then they’ve probably got some huge assholery going on.

AH: What do you consider your greatest singularity?

LL: Oh boy. I don’t know. I always think about my animating subjectivity. My writing is not always from life. Some things that I write are deeply fictional. And some things are so close to reality that my mom does this cute thing where she’ll call me and be like, “Is that your friend? Which one of your friends was that?” And I’m like, “Mom, [laughs] I’m glad you read my work but please don’t ask me that.” She does it because she recognizes the story but also because that’s part of the pleasure.

So, if I have a voyeur’s eye, I think I also have an exhibitionist’s impulse. I like to dare people. One of the ways I do this in my work is by putting something out there and suggesting, What if I make you look at this? Or, what if I’m reading live and you have no choice but to think that it’s me and maybe it’s me? I guess that it is provocative. People have called me a provocateur, which is very flattering and nice, especially if you’re from the Nineties [laughs]. It’s where I get my bravery from. And I think my work gets better the further into that I go. And it frees me again from the fiction question. I have a story called “Valentines” in which the protagonist locks herself in the trunk of a stranger’s car—which, is totally fiction, I wish I had balls like that—but while she’s in the trunk of the car she gets to think about all the people she’s been creeping on her entire life and her relationship to her sexuality. I have a hard time imagining that people who know me even halfway well could read that and not see me there.

I like the discomfort. I like making people uncomfortable. I hope that my writing lets people see something that is maybe inaccessible or scary or just strange. When I was a teenager, people always seemed to like my own weird fractured subconscious whenever I let it bubble up, and I think my work gets better the less I try to contain it and build structures around it. This is hard for me, because I’m kind of a control freak. In that way it’s also kind of a personal project because to really let it out and let it go is scary. What’s scarier for me is the possibility that I won’t do it well. But I’ve also been lucky because no one—maybe one or two people in my life—has ever raised a concern and said, “Is this me in this thing?” I haven’t ever character assassinated anybody as far as I’m concerned. That’s my primary metric. One guy Facebook unfriended me, though.

AH: What you are working on now and what your bigger picture goals are for the future?

LL: I have one more year of my PhD. I could have graduated this year but I’m not going to. It’s wild that it’s ending. I can’t believe I’ve been here this long. If this coming year is my final year, which I indeed think it should be, it will be seven years. I’ve never taken a break between school programs, so when I graduate I totally expect to have some kind of midlife crisis because I’ve not been a student—although these PhD years have been more like having the support of a friendly institution than participating in a traditional studenthood. It’s funny to me now, because my cohort came in with five years of funding, and I was like “why can’t I do it in four?” and they said, “you can graduate in four … if you have a job.” And I totally didn’t understand how that worked at all.

It took me a really long time with my novel, which is called Jutland Gothic. I finished the first draft, after four years of suffering, last summer at the Djerassi residency and then in the summer I did a manuscript consult with Mat Johnson at the Tin House Writers workshop—he picked my book, which was very flattering to me—he was the first person who had read it other than my sister. It came out so long. It came out 750 pages, which is not how long I wanted to be. For him I cut like 100 pages, and he had some suggestions, and some of them were really radical, including changing the race of one of the primary characters. I’d been in the woods with it for so long that I was tempted to make his edits and just be like “Okay! This is what this person that I deeply admire thinks, so let’s do it!” But I couldn’t just then because I was too busy, and I’m actually really glad because it gave me some time to think about it and I realized that certain things about the book I did want to keep the same.

I also, in that time period, had a dream come true experience with the writer Darcey Steinke, who has been a big influence of mine since I was a young teenager. Funnily enough she was a suggested Facebook friend for me one day, so I wrote her this goofy fan letter and she wrote back and ended up inviting me to review her new book, Sister Golden Hair, which came out last year. That was really beautiful because when I read it I discovered that her book was arranged quite similarly to the way I had arranged my book, which is told in three sections, each named after a primary character that the narrator has really fixated on and deeply loved. It felt like an affirmation of this thing I’d been doing, really in the dark. So, on Valentine’s Day, I cut another 100 pages and turned the book over to my faculty advisor, Aimee Bender. I’m hopeful that she and a few other people can give it a good read and I can find an agent and sell it. I still hope that my first book will be published, but I suspect it won’t happen until I’ve sold another book that makes readers interested. It’s interesting because when I go back to that book, which is called Peculiar Qualifications and set in the suburbs of Chicago, I’m never embarrassed of it, which is what I always expect. It’s not the kind of writing I do now, but it’s still strong. I still think it’s a book. So I’d like to see it published. I have two short story collections, one of which is pretty close to being done and one of which could be done. The undone one, Girls and Punishment, is actually named after a quote from the posthumously published Bolaño novel The Third Reich: “I probably dreamed about girls and punishment, the way all boys that age do.”

AH: That’s a great title.

LL: Yeah, and I think about calling it Girls in Punishment: A Romance [laughs]. For a long time I haven’t written stories that I’d like to, or pursued critical projects that I’d like to, because I couldn’t until the novel was done. I do think that things can be truly “done.” And I’d like for at least one of those things to be truly done, and ideally published. My next novel is called My Father the Dictator, which exists only in outline form. It follows the experiences of a female heir to a totalitarian regime, which is a highly fictionalized state, but I describe it as “Putin meets ISIS.” I see that book being written in very short chapters. I’m interested in doing something that’s very different from the novel that I just finished, which has been this drawn-out, kind of psychotic process. For a long time now, I’ve also had this idea about wanting to write a book about the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, on whom I’ve done a lot of research and work.

AH: To finish off, maybe you could talk a little more about your work as a teacher?

LL: You know, the most wonderful aspects of my MFA and PhD has been learning that teaching is work that I enjoy. It’s deeply exhausting and can challenge the writing, but it also gives me a lot of hope and strength. I hope that in my career I’m able to find a teaching position that allows me to focus on teaching and writing in tandem. Surviving my PhD has involved working a crazy number of odd jobs. None of which has been arduous or terrible. I mean, the number of them has been arduous, and that’s where that dream of focus comes in: the tenure track job.

I used to worry a lot. I would obsess about publishing. And I think that obsession was good, because it made me a really active submitter and probably got me published a lot. And I would obsess about book publication, too. I mean it was a huge blow for me when my book wasn’t published. I was twenty- four years old and I had a vision of myself—which I think I’d been encouraged into to a certain extent—as this ingénue writer. That ingénue role, I think for a woman, is hard to shake. There’s a trajectory that makes sense. You believe you’re going to be recognized as what you are. And not having that book get published, not having it get picked up by an agent right out of my MFA, that was actually a blessing—it sounds sappy—but the trajectory is there within me anyway.

I think I have accepted that I can’t really shake this thing that I do. It seems like a pretty beautiful gift because I can’t really think of anything more wonderful and wacky than me being able to write about the obsessive, often erotic turns that my subconscious makes, and other people wanting to read about it. I feel honored by my students and I feel honored by my characters for wanting to hang out with me—to say nothing of my friends and family. It is such a deeply satisfying fantasy, all those book projects I just laid out. I mean, I’m sure I could come up with something else, but those projects sound pretty good to me.

The more I think about it, the more all the fiction I respond to and that I aim to emulate, it all has a really concrete sense of interior place. Understanding the places that your own subconscious goes when it projects and dreams. I started thinking about this because when I was a kid I read the diary of Anne Frank and I visualized the annex where Anne and her family lived, and I remember thinking wow, the description is amazing. And then I realized it was my grandparents’ living room. I remember when I told my mom that she asked if I associated my grandparents’ house with escaping the Nazis and I was like NO! I realized that I was projecting this space into this fictional space. It’s a very weird feely-outy thing to explain, but thinking about how to teach it has made me think about it in writing. If I can plot that internal space then I think I can get away with a lot. And certainly the stories where I feel like they are working really well, the sensation I always think of is that of a snake unhinging its jaw to eat something bigger than itself. I don’t know why, but that’s a very creatively empowering move for me. So I like that feeling: unhinging and unspooling and letting go.

Allegra Hyde is a former prose editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review. For more see: www.allegrahyde.com.