Solid Objects: Shannon McLeod

Tayari Jones keeps a baby food jar of dirt on her desk from Toni Morrison’s hometown. CJ Hauser gifts her students a tiny plastic chicken to pull out whenever and wherever it’s time to write. Writing totems, talismans, amulets—we ascribe many names to the objects we keep close while we write. These objects inspire us, comfort us; they can prompt our productivity, make their way into our writing, or at the very least, serve as a dangling carrot to the world beyond our daily pages.

In Virginia Woolf’s short story, “Solid Objects” her main character grows enamored with a smooth piece of green glass he finds at the beach. “It pleased him; it puzzled him; it was so hard, so concentrated, so definite an object compared with the vague sea and the hazy shore.” The right object can be our own green glass; a raft when we’re treading the slippery shapes thoughts take.

In SOLID OBJECTS, we ask writers about the objects most essential to their creative practice, and what exactly these objects do for their brains.

This edition is written by Shannon McLeod. Shannon’s collection Nature Trail Stories is out now from Thirty West Publishing.

The summer before my first year of college, I spent Saturdays selling baked goods at a farmers market in rural Michigan. When I wasn’t at the farmer’s market, I was living at a yoga retreat, which was more like a religious commune we called “The Ranch.” Nightly meditations were required; alcohol, drugs, and sex were all prohibited on the property; pictures of gurus hung on nearly every wall to remind us of the lives we were to emulate. I was a housekeeper (read: I scrubbed toilets after raw food weekends). Still, the sense of community and belonging was a great comfort to me, especially in young adulthood, when all I wanted was to feel accepted. The property was beautiful, 800 acres of forest on the Pigeon River. I spent lunch breaks swimming in the frothy swirl where the hydroelectric dam that powered the community poured out. Evenings, I hiked trails, spotting deer and the occasional elk.

But the constraints of The Ranch were palpable, and while an 18-year-old craves belonging she also seeks rebellion. Every chance I got to escape the solitude and boredom of my housekeeping duties, I gravitated towards the kitchen. There, the cook and I concocted a way to get a break from our usual jobs each Saturday and spend the day in “the real world.” That summer, the real world was a place I only visited during grocery trips. It was bright, it was exciting, it was maddening if you stayed too long. If I could scrape together the cash, I could even get a Little Caesars Hot-N-Ready.

After we made our case to the manager, we received permission to sell at the market in lieu of our regular duties. The cook and I did our baking on weekdays before making community dinner: she made the French bread, and I made the vegan biscotti. And early Saturday morning, as the sun was just peeking out over the geodesic domes of The Ranch, we headed to town. We spent each Saturday basking in the presence of normal people. We drank coffees out of paper cups and nibbled on samples from neighboring market stalls. We became friends with the other vendors. My favorites were the Mennonite family. The exterior of their sprinter van was painted with all ten of the kids’ names like an advertisement for a small business.

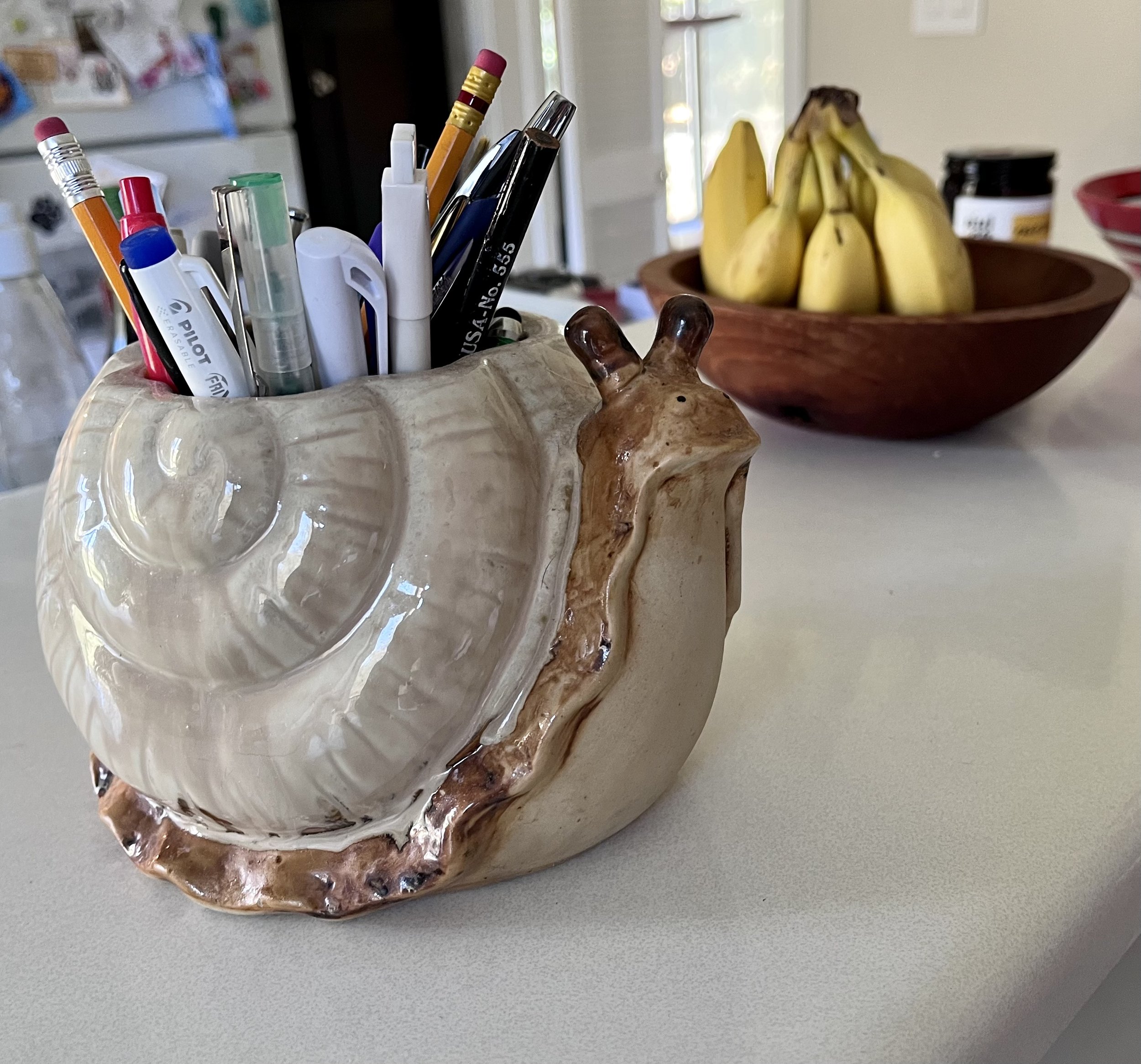

On my last day of the market, I wanted to buy something to commemorate my summer. After the cheese guy from the next stall talked me into it—“You can put it in your dorm”—I bought an adorable planter in the shape of a snail, which was filled with flowers. The flower vendor with the caked-on mascara said, “You’ll have this pot the rest of your life.”

I returned back to the real world, snail pot in tow. I named her Camilla. After the flowers died, I brought her to my dorm. Here, I lived among hundreds of other college students. I blended in and disappeared. I had no community. Life felt chaotic. I froze up in that chaos and spent whole days without speaking to anyone else, despite existing in crowds on the bus, in lecture halls, in the cafeteria. In my tiny room at night I wrote in my journal and listened to CocoRosie. I gazed into Camilla’s cherubic face and missed my summer at The Ranch.

Small creatures captivate me. There’s something meditative about stopping to observe an insect, a bird, a budding tree, a slug. Two summers after The Ranch, I traveled to Acadia National Park in Maine and discovered “Wonderland,” a part of the shoreline where it was said you could sing to the snails to coax them from their shells. I crouched at the rocky tidepools, picked up a shell, and serenaded the snail hiding inside. It emerged, antenna wriggling, as if to say, “I hear you; you found me.” Years later, this experience inched its way into a story in my collection Nature Trail Stories.

Eventually, Camilla and I moved into a student housing co-op, then a shared studio apartment, then another co-op, then an apartment with my future husband, and now our home in Charlottesville. Today my original snail friend sits on my kitchen counter holding the good pens. Everywhere I’ve taken Camilla the snail, she reminds me of my natural pace, the way of life I push against until my body reminds me to slow down. I read slowly, I write slowly, when I’m functioning at my best I move through the world slowly.

Once I built a more permanent home, I started noticing snail tchotchkes in stores. I saw another snail planter on the shelf at Big Lots. I took my measly call center paycheck and splurged on it after much hemming and hawing about its unnecessary cost. Later, I found a jewelry dish with a snail and “Go Slow” stamped into the clay, which I purchased as a birthday gift for myself.

Then my father-in-law found out about my love of snail objects. My husband and father-in-law are similar in their collecting tendencies. Christmas after Christmas I unwrapped little snails while sitting in their living room by the tree. There were clay ones and porcelain ones and metal ones. Ones wearing little hats: a brown one with a fez and a green one in a sun hat. Ones on jewelry, ones for the garden, and many for the bookshelf. He’d get a glint in his eyes and break into a grin when he’d watch me unwrap them.

So my snail collection grew. Little reminders of the outside world in my home, where I write and hide from everything out there. Writing, too, allows me to engage with ideas about the world while avoiding it entirely. Now, most of my snails are clustered on my favorite bookshelf, the one I inherited from my grandparents after they went into assisted living. My husband got a small honeycomb-like shelf to display my snail figurines on the bookcase. This shelf-within-a-shelf is filled with smaller snails. I have what I think of as my lucky snail in the change dish in my car, just below the gearshift and next to my quarters reserved for renting shopping carts at Aldi. A recent favorite is a hand-sewn felt snail filled with beans and cotton, a souvenir from a friend’s trip to Japan. The space on my bookshelves is dwindling. Looking at them, the only objects I’ve made space for in my library are the ashes of my beloved neighbor’s dog (another story entirely) and my snail collection.

I told myself I could stop. I could cut off my snail supply. I even requested “no more snail gifts” from my in-laws. But in the most unexpected shops, I still find little snails that catch my adoration. Small reminders of the outside world, a more natural pace. It’s an impulse purchase in the realist sense of the phrase.

As I write about my snail objects, which mostly lack utility, I think about how much my relationship to snails is like my relationship to writing. Maybe this is my writer’s mind, spinning metaphors from the unrelated debris of life, but I see writing and snails much the same:

I try to talk myself out of loving them.

They take much longer to move than you expect. Every time. No matter how much people talk about how slow they move.

They remind us that time is relative and purpose is imperative—but meandering is too.

My most recent snail purchase was a card for a friend. From Critter Butts, my favorite vendor at the farmers market in my new hometown: a block print of a baby snail riding a big snail's back. The big snail is wearing a party hat.

And I do not regret it.

Shannon McLeod is the author of Nature Trail Stories (Thirty West Publishing, 2023) and the novella Whimsy (Long Day Press, 2021). Her writing has appeared in Tin House, Prairie Schooner, Hobart, and SmokeLong Quarterly, among other publications, and has been nominated for Best Small Fictions, Best of the Net, and featured in Wigleaf Top 50. Born in Detroit, she now lives in central Virginia. You can find Shannon on her website at www.shannon-mcleod.com.