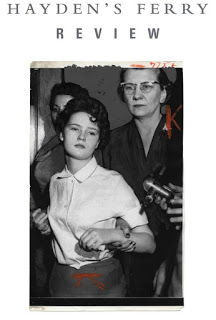

On the Cover: A Review of Christian Patterson

by Lara Shipley, art editor

In the small town where I grew up, my dad was the prosecutor. As a kid, whenever I had the opportunity alone in his office, I would rifle through his desk drawers, pulling out stacks of evidentiary photographs. These were snapshots that appeared at a glance not to contain much at all: broken windows, stains in the carpet, tire tracks, sloppy shots of small homes tucked into the woods. I found them fascinating. I knew the pictures were about things that had happened, bad things, and I thought if I studied them carefully I could discover their story. But the images were too mysterious, and I found that more than a narrative that was simple to parse, I was left with an undefined feeling of unease.

Christian Patterson’s project, Redheaded Peckerwood, plays upon our desire and belief that photographs can tell straight facts. The project contains many photographs reminiscent of those I saw in my dad’s desk: oil stains on the carpet, a knife in the wall, blood in the snow; the residue of violence. But these images reference a killing spree carried out by a teenage couple, Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, in Nebraska almost sixty years ago. Patterson spent five years traveling the route the couple took while running from the law. He made photographs that feel like clues, and the viewer is invited to reassemble these bits of information to make sense of it all. At the same time, he indicates that his images are photographs, not documents of fact. Patterson includes both black and white and color photographs, some of them featuring double exposures and light leaks. He mixes photographs from different languages of photography; the studio, the field, weaving in historic images that he alters and scans of actual documents. The accumulation of all this is a confusing blend of fact and fiction.

The story Patterson’s photographs tell is gruesome. It’s hard to not look for some explanation of how or why two young people from the rural Midwest would kill so many people, many of whom were their own relatives. But looking through Patterson’s images I am reminded of that same feeling of frustration and fascination I had looking through those evidence photographs. If there is a story told here, it is more about Patterson’s own fascination with the crimes and the young people who committed them. The psychology of the crime, he suggests, is more than objects can hold, than photographs can relate.

In the small town where I grew up, my dad was the prosecutor. As a kid, whenever I had the opportunity alone in his office, I would rifle through his desk drawers, pulling out stacks of evidentiary photographs. These were snapshots that appeared at a glance not to contain much at all: broken windows, stains in the carpet, tire tracks, sloppy shots of small homes tucked into the woods. I found them fascinating. I knew the pictures were about things that had happened, bad things, and I thought if I studied them carefully I could discover their story. But the images were too mysterious, and I found that more than a narrative that was simple to parse, I was left with an undefined feeling of unease.

Christian Patterson’s project, Redheaded Peckerwood, plays upon our desire and belief that photographs can tell straight facts. The project contains many photographs reminiscent of those I saw in my dad’s desk: oil stains on the carpet, a knife in the wall, blood in the snow; the residue of violence. But these images reference a killing spree carried out by a teenage couple, Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, in Nebraska almost sixty years ago. Patterson spent five years traveling the route the couple took while running from the law. He made photographs that feel like clues, and the viewer is invited to reassemble these bits of information to make sense of it all. At the same time, he indicates that his images are photographs, not documents of fact. Patterson includes both black and white and color photographs, some of them featuring double exposures and light leaks. He mixes photographs from different languages of photography; the studio, the field, weaving in historic images that he alters and scans of actual documents. The accumulation of all this is a confusing blend of fact and fiction.

The story Patterson’s photographs tell is gruesome. It’s hard to not look for some explanation of how or why two young people from the rural Midwest would kill so many people, many of whom were their own relatives. But looking through Patterson’s images I am reminded of that same feeling of frustration and fascination I had looking through those evidence photographs. If there is a story told here, it is more about Patterson’s own fascination with the crimes and the young people who committed them. The psychology of the crime, he suggests, is more than objects can hold, than photographs can relate.