Interview with David James Poissant

On Tuesday, March 18th

at 8 p.m., writer and Hayden’s Ferry

Review contributor David James

Poissant will be giving a reading at The Tavern on Mill (404 S. Mill Ave.)

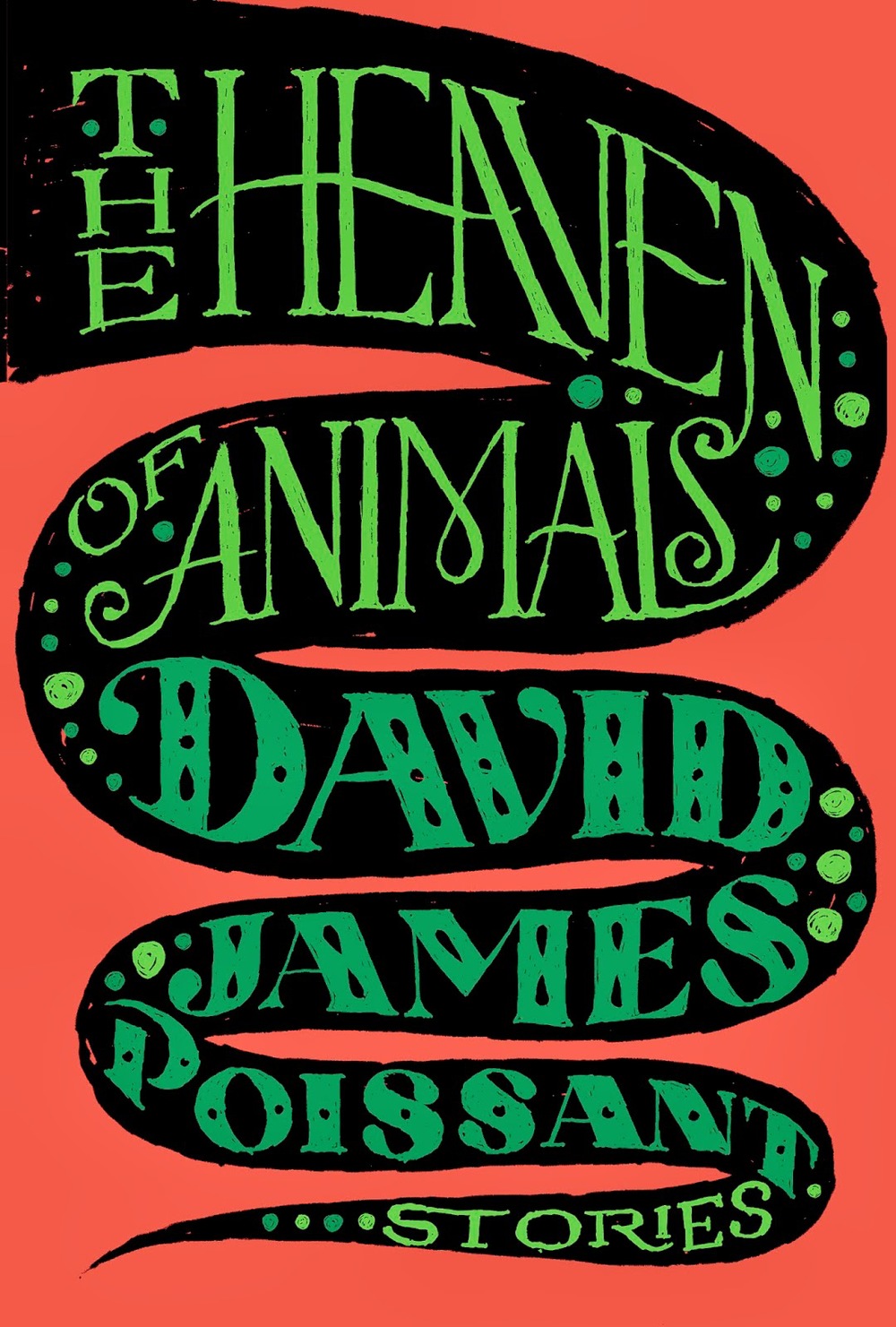

from his debut book, The Heaven of

Animals, a collection of short stories. The

Heaven of Animals will be available for purchase at the reading, courtesy

of ASU Bookstores.

Poissant

teaches in the MFA Creative Writing program at the University of Central

Florida, and his stories and essays have appeared in The Atlantic, The

Chicago Tribune, Glimmer Train, The New York Times, Playboy,

and Ploughshares, among others.

His work has been awarded the Matt Clark Prize, the George Garrett

Fiction Award, the RopeWalk Fiction Chapbook Prize, and the Alice White Reeves

Memorial Award from the National Society of Arts & Letters. His story “The Hand Model” appeared in HFR52.

With The Heaven of Animals just released,

Poissant is already hard at work on his first novel, Class, Order,

Family, forthcoming from Simon & Schuster. Jake Adler recently had an

opportunity to speak with Poissant about his work as he travels the country on

his book tour.

Jake Adler: What are the

central themes of Heaven of Animals? What ties your collection of

short stories together?

David James Poissant: Well, while

there are a number of animals that wander through the stories, I feel like the

central themes include love, loss, and atonement. Many of the narrators in

these stories are seeking to right a wrong, to atone for something they've

done—some cruelty to a family member or loved one. I'm really interested in the

ways by which we hurt those we love most, sometimes on purpose, though often

without meaning to. There is a decent dose of tragedy in the book, but humor

too, and hope. My hope is that some hope shines through!

JA: How long have you

been working with the book and what inspired the collection? Did writing one

story prompt or inspire you to write another? Do you have a favorite story

from Heaven of Animals?

DJP: I wrote the

earliest story from the collection in 2004, and I finished the final revisions

on the book in 2013, so I guess you could say that the collection took me nine

years. But that's a little misleading, since, during that time, I also wrote

and published another twenty stories and several essays, plus began work on the

book that will be my first novel. I wouldn't say that I have a favorite story

from the collection. I think that it depends on the day and my mood. I know

from giving lots of readings that “100% Cotton” and “What the

Wolf Wants” make for the best out-loud reading experiences for audiences.

Otherwise, I don't know. Picking a favorite feels like trying to decide which

of my kids I like best!

JA: What can you tell

me about your forthcoming novel? How have you approached it differently

than Heaven of Animals? How do you know when a story is becoming a

novel, rather than simply a short story?

DJP: So, I wrote

“Venn Diagram” and “Wake the Baby,” two of the stories in The Heaven of Animals, with no plans to return to those characters.

But I just couldn’t shake them. The novel picks up about thirty-five years later.

Richard Starling is a physicist. Lisa Starling is an ornithologist. They’ve

spent the bulk of their careers at Cornell and enjoyed summers at their lake

house in North Carolina. Their sons, Michael and Thad, are now grown and in

their thirties. Michael is a pharmaceutical rep married to an elementary school

art teacher. They live in Texas. Thad lives with his boyfriend, an

up-and-coming painter, in Brooklyn. Then, one summer, Lisa calls her sons out

of the blue to inform them that she and Richard are retiring early and that the

lake house (which was always supposed to stay in the family) will be sold. The

sons and their partners are summoned to North Carolina for a final week

together as family, and, as tends to happen whenever family gets together for a

week, things get tense. When a tragedy strikes the lake community, it

reverberates through the lives of these six characters in a way that causes

them to question not only why they’ve come here, but what comes next and

whether they still want what they thought they wanted when the week began.

It’s a long novel

(growing ever longer) told in six roving, third person, limited omniscient

viewpoints. I think that I always knew that it would be a novel, just based on

the scope of the story I wanted to tell, which felt larger than the constraints

of a story or novella-length work.

JA: As a Creative

Writing MFA professor at the University of Central Florida, what sort of trends

do you see rising among young writers today? What do your students tend to

struggle with most, and what have they done that has surprised you?

DJP: What's great

about the writing in MFA programs today is that I don't see many

"trends." People sometimes worry that MFA programs churn out writers

who all sound the same, but that hasn't been my perspective, at least not based

on my limited experience. I have students writing stories and novels, magic

realism and psychological realism, tragedy and comedy, and everything on the

spectrum from traditional to very experimental. It really runs the gamut, which

is great. We have good students here, hardworking and committed writers. It's

really an honor to get to work with them.

JA: What advice could

you offer Creative Writing undergraduates or young writers seeking to apply for

MFA programs?

JA: What advice could

you offer Creative Writing undergraduates or young writers seeking to apply for

MFA programs?

DJP: Getting into

MFA programs is getting harder and harder. My best advice is this: You can't

charm or joke your way into a program with your cover letter. Better to take it

seriously and be professional about it. Likewise, reference letters are important,

but they seldom make or break an application. I'd say that 95% of the decision

on who gets in at UCF (and, by extension, probably most MFA programs) comes

down to the writing sample. Put forward your best, most polished work. Really,

the secret is that there is no secret. We're all just looking for the best

writers we can find. And, of course, that decision is subjective, so best to

cast a wide net. For example, when I applied to programs in 2004, I applied to

twelve and only got into one, the University of Arizona. But, if the program's

the right program for you, all you need is one.