Jari Bradley (they/them) is a San Francisco native. They are the recipient of an Inprint C. Glenn Cambor Fellowship and a Cave Canem fellow. Their poems have been published in Callaloo, Virginia Quarterly Review, Academy of American of Poets (Poem-A Day), and elsewhere. They are currently a PhD candidate in Creative Writing and Literature at the University of Houston and poetry editor for Gulf Coast Journal.

Interview conducted by HFR Intern Nikolai Ryan

Nikolai Ryan: Feel free to answer this in whatever way you see fit and are comfortable with—in regards to gender, how would you describe yourself?

Jari Bradley: For many years I regarded myself as genderqueer, particularly a Black genderqueer person. I now identify as a Black transmasculine genderqueer individual. Though, even now I hold out the possibility of those identifications changing and continue to acknowledge that I am still finding language for my gender-based identifications/intersections. I take very seriously the writings of Hortense Spillers and Christina Sharpe who both theorize the process of the TransAtlantic Slave Trade, the hull of those ships, and the all-consuming weather or climate of anti-blackness surrounding those vessels of stolen human cargo as having irrevocably transformed Black being into genderlessness. So at the base, Blackness and the atrocities of slavery have historically undone the designations of gender on behalf of the once enslaved, or my ancestors in other words. Saidyah Hartman’s notion of the wayward is reminiscent of my unorthodox experience of girlhood, which was a kind of boihood. I was a tomboy that never grew out of what some would call a phase. In this way, I had always been wayward as a result of failing at socialized and socially accepted/expected performances of femininity. So it is this history alongside leaning more toward the masculine spectrum of the binary that has led me to know myself as a Black transmasculine genderqueer person, in all the various ways those identities blend within and contradict one another.

NR: How do you engage with the idea of gender in your life, e.g., in your personal expression, in your relations with others, in your writing and other creative pursuits?

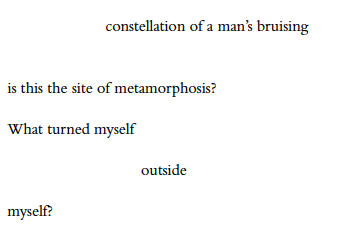

JB: In my personal life, I am considered largely masculine in representation, often being mistaken for a cisgendered man or being told by some that I supposedly am able to “pass” as one. This passing is inconsistent in its “success” as I still get “ma’am” and “miss” from time to time. My gender is engaged by others largely by how I am perceived, as my physical composition would signal to some, maleness. I however understand myself as a fluid individual that feels cunt in certain company and like that dude in others. Ultimately, though my gender expression is majorly masculine, I know myself to exist as myself, which is some amalgamation of both those ends and what exists in between. I try to reflect this in much of my work, the slippage of gender and its fluid nature. How this slippage contributes to the consistent expectation people in my life and socially place on gender and its performance. My life was and in many ways still is plagued by the expectation of domestication as is expected of those of us born female at birth. I write about the ways in which masculinity equates to complications with vulnerability and its attachments to socialized/private violence. I am always seeking to investigate the binary in my work and how those categorizations contribute and/or disrupt the ways many of us have been conditioned to perceive and treat others and how we ourselves are perceived and treated by others.

NR: How does your identity impact your writing, whether it’s explicitly about identity or otherwise?

JB: I kind of touched on this in the previous questions but identity, like gender, is really to me, all wrapped up in the phenomenon of perception and being perceived. There unfortunately is a script we walk into when we step out into the world or post versions of ourselves online, ones that we did not write and ones that are out of our control in as much as we can do anything about them being held. There is so much currency in being deemed desirable, worthy, and are given the chance to be seen as a human being. As it relates to existing in the world fat, Black, and nonwoman, I am not given the opportunity (historically or contemporarily) to be seen as human. In many cases, bodies like mine are subjected to intense fetishization, and those things are inextricably linked to how I see the world. The markers placed on my identity as unruly is what I essentially base my poetics on and around. The inability to assimilate, to be a member, my intersections automatically make me insubordinate or wayward or non-compliant. Simply existing, as I am, marks me as “other,” which has fed much of my writing practice as I work around the gaze or how I am perceived vs. how I perceive myself. There is power in being able to say “I know exactly what you think I am, and I’m telling you you have no idea about what I am or who/what you are either.” There is power in upending what is automatically deemed “natural” while simultaneously providing examples of the common everyday occurrence and existence of the “unnatural.” This is what much of my work seeks to do, undo what one already thinks they know when they come to my writing, much like when they perceive my body. My work engages the very real possibility that other ways of seeing and being exist, that other worlds are not only possible but are happening in real-time.

NR: What do you think are the most important things we can be doing as writers and readers to amplify TGNC voices of all intersections?

JB: There needs to be a serious commitment to platform the voices of TGNC voices, and not just lip service about it, but it needs to be put in practice/praxis. Particularly those TGNC voices that are cast to the margins as a result of how they and their voices are perceived as marginal. Especially by readers and writers privileged enough to provide publishing/reading opportunities for TGNC poets. Mutual aid is also a crucial means of support for TGNC poets, many of whom, whether affiliated with institutions or not, face unprecedented and significant lack of financial support which impacts their ability to actually create the art they are sought out for. And that is not by accident, rather it is by design. So it is imperative that when we see the most marginal among TGNC voices campaigning or even just showing up on the timeline, that we as a readership and also as platforms do what we can to fund those writers, many of whom are struggling to pay for rent, food, and see doctors. Mutual aid is crucial to the literal survival of these artists, myself among them. By providing for one another in this way, we ensure the possibility of community-led and self-sustained projects meant for our communities to continue to thrive, primarily providing avenues for our communities outside of the academy and/or other institutions that we have seen devalue and dismiss our concerns as literary citizens of the world. It really is up to us to cultivate the ecosystems necessary for the work of marginal TGNC writers to thrive so that whole literary communities can prosper outside of the hegemonic and detrimental neutrality of certain institutions and organizations that have in these most urgent times censored, shelved, and ultimately have had a hand in stifling the work of marginal TGNC writers.

Three Poems by Jari Bradley

orginally published in Issue 66