Solid Objects: Sarah Ghazal Ali

Tayari Jones keeps a baby food jar of dirt on her desk from Toni Morrison’s hometown. CJ Hauser gifts her students a tiny plastic chicken to pull out whenever and wherever it’s time to write. Writing totems, talismans, amulets—we ascribe many names to the objects we keep close while we write. These objects inspire us, comfort us; they can prompt our productivity, make their way into our writing, or at the very least, serve as a dangling carrot to the world beyond our daily pages.

In Virginia Woolf’s short story, “Solid Objects” her main character grows enamored with a smooth piece of green glass he finds at the beach. “It pleased him; it puzzled him; it was so hard, so concentrated, so definite an object compared with the vague sea and the hazy shore.” The right object can be our own green glass; a raft when we’re treading the slippery shapes thoughts take.

In SOLID OBJECTS, we ask writers about the objects most essential to their creative practice, and what exactly these objects do for their brains.

This edition is written by Sarah Ghazal Ali. You can also read her work in Issue 70, out now.

I’m prone to bad dreams, and they often boil down to anxieties around communication. In one, my husband decides to leave me and refuses to tell me why. In another, I spot my never-known grandmother across a field, but she won’t look my way no matter how loudly I call to her. My mouth is full of seawater, or taped shut, or too slow to hinge open. Many nights have passed so deprived of sound I wake up convinced that I’m invisible, that I've vanished.

These dreams are probably reflections of how little faith I have in my voice, in its singularity. Can I call it mine? I am quick to adjust my speech to match the tenor of whomever I’m speaking with. I hesitate to say anything, really, with authority. There’s an overwhelming impostor syndrome I have even walking through the world, moving through its humdrum commotion.

The future takes its cue from the past. My past erased by a great partition. I couldn’t tell you with confidence what regions my grandparents are from in Pakistan, or what their lives were like. I’ve inherited silences, and they push ceaselessly against my throat. Even writing this, I pause after each sentence: is this true? Who could I check with? Six different occurrences of “I think” I’ve now effaced. Even when I share something that I know with certainty, I qualify it, I doubt myself, shrug, I could be wrong.

My writing process I might more accurately call my self-soothing process. The quiet of a blank page guides me toward hearing myself. There, there, voice. I’ve found you a place to perch. On the page, I’m not free of doubt, but free to trace the contours of my thinking.

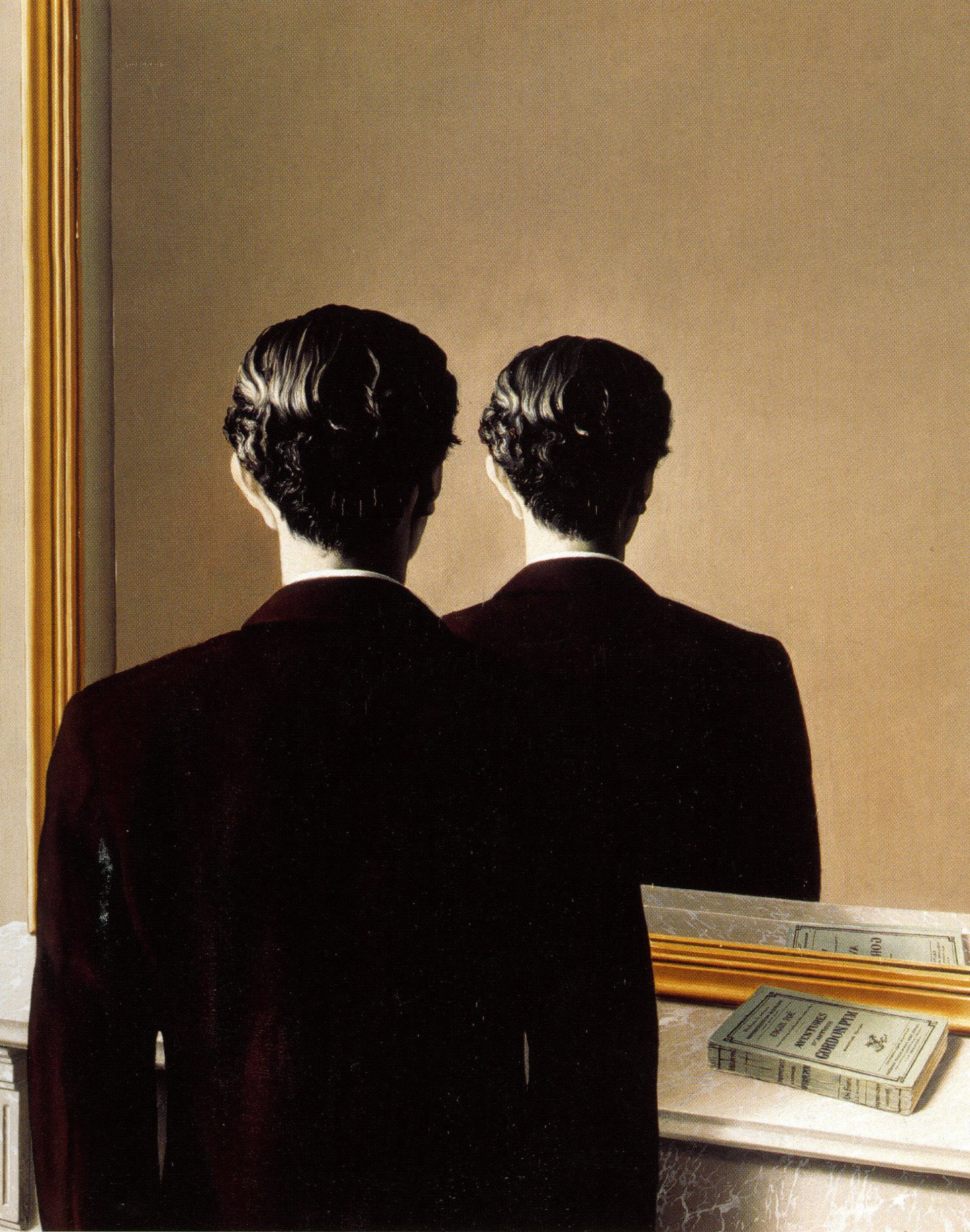

I write in Notion, a note-taking workspace that has been indispensable for drafting, making to-do lists, and containing the ricochet of my uncertainties. On the home page, I keep the image of a 1937 painting—La reproduction interdite, or, Not to Be Reproduced by Belgian surrealist René Magritte. Whatever I’m doing at my desk—writing, daydreaming, reading—I keep the painting full-screen on my monitor, and glance back up at it from time to time. In it, a man’s back is turned to the viewer as he gazes into a gold-trimmed mirror on a mantel. Where his reflection should be, we find in the glass, again, his turned back, the nape of his neck. A novel on the mantel, however, is reflected correctly.

The painting is a portrait of the poet Edward James, a friend and patron of Magritte’s. I first encountered it in a college art history course, right around the time I began writing poetry in earnest. Of course the portrait of a poet would be inscrutable. Of course the poet is moored to an unending moment, trying to meet his gaze, but instead finding his own back turned to him. When I’m stuck, I use this title as a placeholder in drafts. More than half of the poems in my first book began as “Not To Be Reproduced” poems; their true titles emerged much later.

In this likeness of James, I see Abraham’s turned back, leaving Hajar in the desert. I see the tireless, beautiful work of angling toward my full, future self. On days when I am immobile in my own unknowing, I see a reminder that the mirror might be a dead end—that I should look out the window instead. On days when I am grieving the gaps in my lineage, I see a suggestion—my elders aren’t turned away from me, but toward something they are waiting for me to notice, too.

With this painting in my peripheral, I have the space to look without being looked at. His non-gaze keeps me company, unwatched, and so unabraded. Lucille Clifton: “what did i see to be except myself?” There, there, voice. I’ve found you a place to be.

Sarah Ghazal Ali is the author of Theophanies, selected as the Editors' Choice for the 2022 Alice James Award, and forthcoming with Alice James Books in January 2024. A 2022 Djanikian Scholar, her poems appear in POETRY, American Poetry Review, Pleiades, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She is a Stadler Fellow at Bucknell University and poetry editor for West Branch. Find her at sarahgali.com.