Whose Secret

You wrote us a letter, but no one knows what it said.

David finds it first. He can’t read Korean because no one bothered to teach him. He sets your letter on fire and flushes the ashes down the sink. When the police come by and ask if you said anything or left anything behind, he shakes his head. He tries not to touch the lighter in his pocket.

He only tells me about your letter months later. And he seems so ashamed that I can’t find it in me to be angry with him. I know my brother. If he burns your final words, then you never wrote them down. If he keeps them a secret from himself, he can pretend they never happened.

Somewhere, he wants to believe, you are still leaving letters for your children to find.

What is a secret? A story we’re not supposed to tell?

The word itself has roots in the Latin participle secernere, meaning “to separate” or “to set apart.” In other words, a secret is a divide. A one-way mirror with people on either side: those who know the secret and those who do not.

I get into another fight with David and our father tells me that his older sister never picked fights with her younger brothers. 아빠’s older sister was at the top of her class and captain of the track team and could play ten different instruments at the same time while reciting the Bible backwards. In my first memory of my aunt, I am in elementary school. She takes my face by the chin and tilts it up so she can examine it from all angles like a horse trader. “Your face is lopsided,” she says. “You’ve been chewing too much on the left side of your mouth.” She terrifies me but I want so badly to please her.

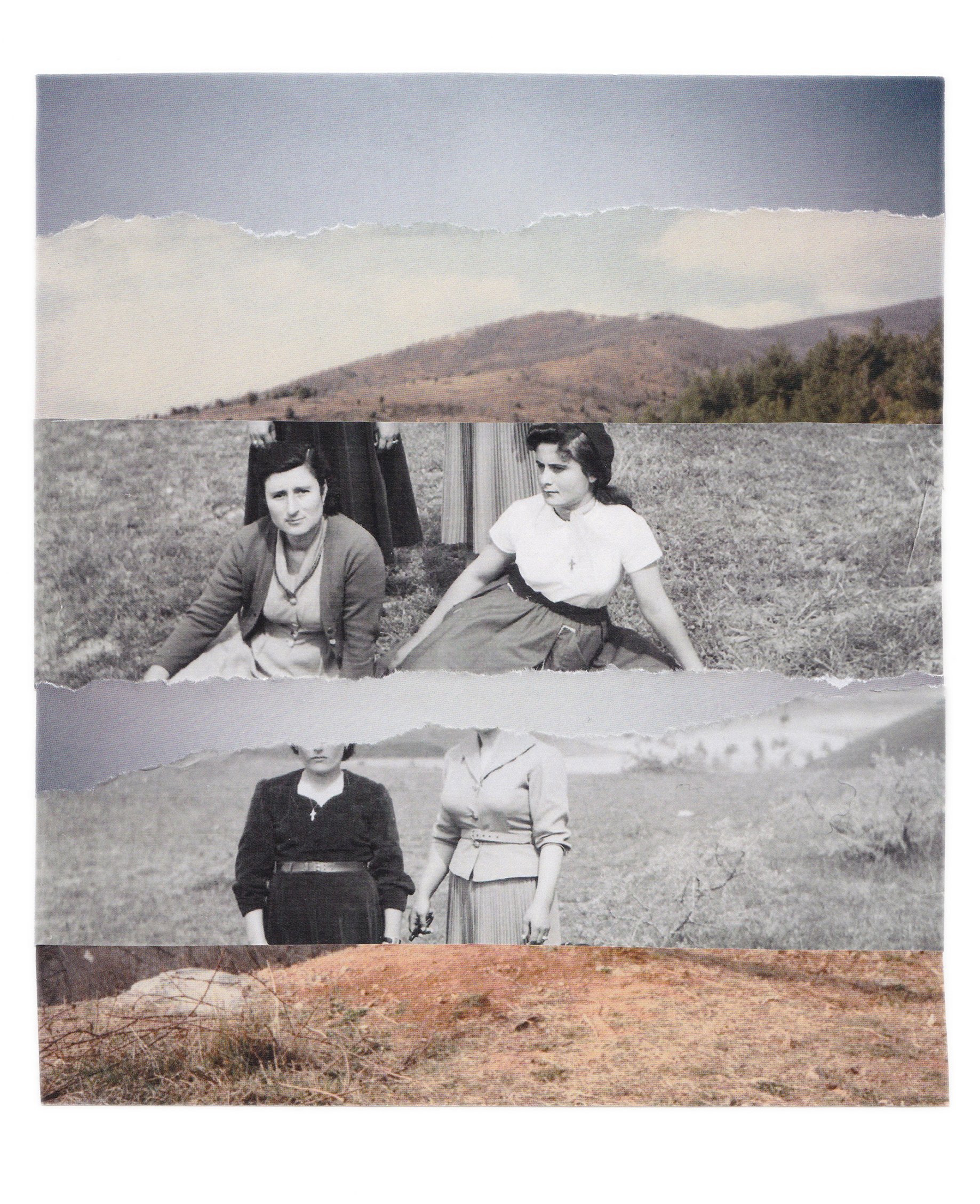

Anthoula Lelekidis, Two generations ago

I was in middle school when 아빠 let slip about a second sister.

“Who?” I said.

He was driving me somewhere and didn’t look away from the road. “Well,” he said, “she’s not really part of this family anymore.” Because he didn’t say anything else, I thought she must have done something really bad. She must have been a bad woman because nobody talked about what she did or what happened to her. Nobody talked about her at all. She’d been separated from the family.

By traditional Korean standards, you were a bad woman. You had your ears pierced and you smoked cigarettes when you thought no one was watching. You drank too much, you were depressed.

You died too soon.

엄마. Because you were a bad woman, you are now our secret.

I don’t remember the last words I said to you. I don’t read our old texts because I’m terrified the last thing I ever sent you was something asinine like Did I leave my earphones in the car?

I go home for spring break and we have a fight. We have another fight and I never remember how they start, but I always remember how they end. This one is no different. I end up in my room, lying on my back and fuming at the ceiling when you open the door.

“No one in this family cares about me,” you say. “If I died, you’d be glad I was gone from your life. I hope you have a daughter who makes you suffer the way you’ve made me suffer.”

I roll over onto my stomach to look at you. I can’t take you seriously when you’re like this. How many times have I heard those lines? By now I’m old enough to know that in a fight, the goal is always to win.

But you have a trump card this time. You hold up your wrists—I told 아빠 and David to keep it a secret, I didn’t want to bother you while you were at school—and then I see it: a partially healed scar. Shorter than I would have expected, almost like stigmata.

I think you’d hoped for some kind of reaction. I think you’d hoped I would start weeping or fall to my knees. Instead I do neither of these things, because I don’t want to let you win like this. I just stare back at you, and something inside of you must split open like a gourd.

“Sometimes I don’t even think you’re human,” you tell me.

That’s the last conversation I remember us having.

A few days after spring break, I get a phone call from 아빠. “Hello?” I say, walking across the quad from my 9:00 a.m. class. He spends some time asking about class and how I’ve been and then says, “Are you busy?”

I have an odd feeling like I’ve been expecting this phone call. Last night there was a heavy rain. Today yellow gingko leaves plaster the sidewalk like ruined origami fans.

“No,” I tell him. “What happened?” He tells me you had a small accident and that you’re in the emergency room. It’s not serious, he says. His voice is light. He makes it seem like you just have a bad cold. Would I like to come see you?

My college campus is twenty minutes away from home. I don’t have a car, so while I wait for 아빠 to pick me up, I play mental games with myself. Would he have called unless it was really bad? How bad did it have to get before he decided to call? Are you dying?

아빠 pulls up to the sidewalk. “Why do you look so unhappy?” he says when I get in the car. I don’t know what to say to this, so I say nothing. He tells me not to worry so much. You fell down the stairs and hit your head. You’ve been in the ICU since Monday but the doctors induced a coma and you’ve stabilized.

In the ICU your eyes are closed. You look so peaceful. Water retention has given you a youthful appearance. A nurse comes in and fiddles with some dials on the ventilator. “Where did she hit her head?” I ask, because I don’t see any swelling or contusions. The only indication that you fell is a neck brace.

The nurse looks at me, confused. “I didn’t know she hit her head.”

I dimly register that this is weird. Something is not adding up. But I don’t want to turn and look at it yet. You’re breathing and your heart is beating steady and that’s enough for now. Just for a bit longer, I want to keep pretending.

Why can’t the people in our family tell each other anything?

A few years ago, I won a contest and some money for a story that I’d written. In the story, a mother who is an artist flees her husband and burns her art along the way. She takes her daughter with her and they road trip to the other side of the country. But her daughter just wants to go back home. She worries about her father.

I didn’t tell anyone I won this contest except for David. He read my story and said, “Isn’t this about Mom?” “No,” I said. “It’s not.” It’s not, I told myself, though you were an artist and one day I came home from school to find a plume of smoke behind the house and when I ran to the backyard, I found you burning piles and piles of your art. Old art, burnt art. Forgotten art.

아빠 found this story online recently. He said that he thought the story, in which the husband is abusive, was about him. We see in ourselves what we expect to see.

I told him the same thing: No. I made it all up.

A professor once told my friend, “Katherine has been writing about her mother for as long as I’ve known her.” In the first workshop I took with him, I wrote three stories, all about mothers. You never asked to read my writing and I never offered to show you, but I wonder if you tried to guess anyway.

I took more workshops and the mothers began dying. One got esophageal cancer, one died in World War II. Another overdosed on medication. “I can’t stop writing stories about dead moms,” I said to my professor. “Have you noticed that? I keep finding ways to kill them off or make them disappear.”

“It just means you haven’t figured out what you’re trying to say. You’re writing in a spiral, getting closer and closer to the core of it.”

“But what if it just means I’m afraid? What if that’s all I write about because I don’t know anything else?”

I don’t remember what he said to this.

아빠 drops me off at school and says he’ll be back later that night. I attend the rest of my classes. I go for an eight-mile run. I peel a mango but can only eat half. We head back to the ICU after the sun has set.

There’s a doctor in the room this time. I’m holding your hand, thinking this is bad but this is not permanent. When you wake up, things will be different. I’ll be a better daughter. I’ll let you win the fights.

I don’t remember this next part either. I must have asked a question and the doctor must have responded with something I wasn’t expecting to hear. “What are you talking about?” I ask him and then I look at 아빠 and back at your neck brace and realize that I’ve been living on borrowed time. “What happened to her? Didn’t she fall and hit her head?”

The doctor glances over my head at 아빠, and the look on his face is strange. He says, carefully, “Your mother was very depressed for a long time.”

Okay, sure. I know this story. I’ve written this story.

I ask the doctor: “Is my mother going to die?”

He is honest. He tells me that anoxic brain injuries are often severe. “But there are people who recover,” I say. “After five or ten years, they wake up from a coma. I’ve read about that in the news.”

“Not like this,” he says. “Not with this level of damage. I’ve never heard of it happening before.”

I back out of the ICU and run to the car. 아빠 follows me and starts the engine. He turns on the heater. At a time like this, he does not want me to feel cold.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” I ask him. “Why didn’t you tell me what happened?”

“I’m sorry,” he says, and he seems so lost, almost like a little kid. “I didn’t want to scare you. I wanted to protect you for just a little bit longer.”

There is so much I don’t remember. In the moment, I didn’t know how I was supposed to live with it. I didn’t write anything down because I couldn’t imagine there would ever be a time when I’d want to look back and remember how it all happened. Perhaps in this way, we are not so different.

I move into the ICU. There’s a window seat by your bed, and I turn it into a bed of my own. The nurses are so kind. They bring me sheets and blankets and pillows. I’m not supposed to bring food into the ICU but they don’t say anything when I eat granola bars for dinner and stuff the wrappers in my bag. I keep a vigil by your bedside and imagine that as long as I don’t fall asleep, I can keep you alive. I fall asleep anyway. I fail you again, night after night.

아빠 comes by frequently but he can’t stay at the hospital because he needs to look after David, who is still going to school. David doesn’t come by very often. During one of the few times he does, he just pats your arm and heads back to the waiting room.

아빠 tells me that the family has decided not to tell people the truth. I have already told my closest friends, but I don’t mention this. The family has decided to keep the truth a secret. Because of the shame that comes with a suicide, I assume. He says we will tell people the same story he told me. You fell down the stairs, you hit your head. I tell him the story is a bad one, it doesn’t make any sense, but he says it’s too late to change it now.

Marian comes to visit you in the hospital. She holds your swollen hand and strokes your wrist. “Oh, Jung-eun,” she says, softly. “What’s happened to you?” She wonders why you’re wearing a neck brace but she doesn’t seem to be looking for an answer.

Others are more suspicious. I go home to shower and change my clothes when Esther’s mother and Rebecca’s mother ring the doorbell, bearing a box of Korean pears. I lead them into the kitchen and take the box from their hands. Our fridge is full of sympathy casseroles. I don’t know where I’ll fit an entire box of fruit.

“It’s so strange,” Rebecca’s mother says. “How did she hurt her neck so

Anthoula Lelekidis, Livaditsa, Greece

badly? Just from falling?” Esther’s mother shakes her head. “She was healthy. She was young. Why couldn’t she stop herself?”

They look at me, expectant or maybe accusing, but I turn away from them and keep trying to find space in the fridge for the pears.

Most of the time you’re sleeping—sleeping, because it sounds better than vegetative—but sometimes you open your eyes and whimper or twitch. You seem so scared. When you look at me, you start crying. “Her brain is just irritated,” the doctor says. “It doesn’t mean anything.”

When my friends find out I’m staying at the hospital, they offer their company. I turn them down. I don’t want to make anyone feel awkward. What are you supposed to say to someone whose mother is drooling on a hospital bed two feet away?

Three people ignore me and come anyway. Once, you told me that people have different kinds of luck. Some people have good luck with money, for instance. Others always seem to be at the right place at the right time. “What kind of luck do I have?” I asked, and you told me that I have always been lucky with people. I have always managed to find the right people, no matter where I am.

Orli drives to the hospital at midnight the night I find out the truth of what happened. She stays awake in the waiting room until dawn and drives back to school for her 8:00 a.m. class. Darby smuggles me an icebox filled with sandwiches and cookies and a steel water bottle of vodka. She knits beside me while I try to edit another dead mom story. The mother is still dead in the story but I am trying to make the daughter less selfish.

Justin spends the night. When he steps into your ICU ward, I think wildly, for one hysterical moment, this will be the first and last time I ever

bring a boy to meet you. He studies for the MCAT while I read a book. At two in the morning, we walk around the hospital to stretch our legs and eat chicken nuggets from the cafeteria McDonald’s. We cram onto the window seat together, heads on opposite ends, and he puts his hand on my ankle and holds it the entire night.

Two weeks after you’ve been in the ICU, the doctor tells us we have to make a decision. She tells us that you’ve developed pneumonia and our options are either to let you go or cut a hole in your stomach and hook you up to a feeding tube for the rest of your life. She confirms that there’s no chance of recovery from brain damage. Your gaze flits around at all of us, wide and erratic, and a decision like this shouldn’t be so easy to make but I think we already made it a long time ago.

In the summer, I go to Korea and spend time with your sisters. They take good care of me. We visit the graves of your parents in the mountainside and I cry more than I ever did when we first laid them to rest. I wish we could have put you between their headstones, buried you in this mountain blossoming with wild cosmos and forget-me-nots.

I visit 아빠’s side of the family, too, which means I stay with his oldest sister. She doesn’t check my face for imperfections this time but she still intimidates me. Whenever I use the bathroom, I count out the squares of toilet paper in case she accuses me of being wasteful. My grandmother is in the hospital with a broken hip, a complication of late-stage Parkinson’s, and we visit her every few days with milk bread, soft rice cakes, fresh fruit.

“By the way,” my aunt says, “I’m very sorry to ask this of you. But we think it’s best if you don’t mention what happened to your mother.” I assume this means my grandmother believes the same story everyone else has been told, but my aunt hesitates. No, they have not even told her that you died. She is old. It would cause unnecessary anxiety. My aunt wants me to pretend that you are still alive.

So when my grandmother asks me, “And your mother? Is she in good health?” I say, “She’s doing well. Yes, she’s doing very well. Thank you for asking. ”What is the point of this anyway? Have I done a bad thing? You wrote a letter for us that no one will ever read. I’m writing you a letter that you will never read. We made you a secret and I don’t know who it belongs to anymore.

A year passes. I graduate school and move to Baton Rouge for more school. When I go back to Atlanta for the holidays, I stay mostly with my friends. I should spend more time with 아빠 and David but I don’t like being at home. They fight all the time now. David wants to go out and 아빠 wants him to focus on school. David smashes his glasses and 아빠 breaks his phone and I hate the sound of it all.

David has started missing classes and doing drugs. He stays out late, comes back at two or three in the morning. People worry about David because he lost his mother at such a young age, and 아빠 worries about David because he thinks his son will be a delinquent.

I am worried about my brother because I think there might be something very wrong with him. One day I’m looking for a boxcutter to open a package but when I find it, the blade is missing. “Oh,” David says, peering over my shoulder. “We had to take it out after Mom. You know.” Your son was only fifteen when he found you bleeding from your wrists in a bathtub. Only a freshman in high school when he found you in the basement with a pillowcase around your neck.

David gets his license. He regularly drives while high and the smell inside the car is unbearable. He laughs and calls it the trap car, which makes me want to hit him. I want to see him cry. I want to know that my brother is still a person capable of crying.

The Northcutts invite us over for Thanksgiving. They’ve been so good to us. Marian keeps a framed photo of you above the sink in the kitchen. Last year at their annual holiday potluck, Nelson stood on a chair and gave you a

toast. Thanksgiving dinner is just family, but they’ve invited us over, and Marian carries in your photo from the kitchen. She sets it in the dining room so you can eat with us too, and it’s not so different from the Korean ancestral rites when we burn incense and offer food and liquor to your image.

When we get back home, I go to my room and David goes to his room and 아빠 goes to his office room. We are living separately under the same roof. I hear arguing and try to ignore it until there’s a crash from downstairs. The door to the garage is flung open and 아빠 lies sprawled out on his back. There’s a hole in the drywall and David is screaming.

“What’s going on? What happened?” 아빠’s eyes are open but he’s not making any sense. He keeps talking about wanting to buy some beer while behind me David babbles, “I was just trying to go to my friend’s house. He wouldn’t let me go.”

Not again. Because I don’t know what else to do, I call 911. As soon as the operator picks up, I feel stupid. “I’m sorry to bother you,” I tell her. “My father. He got into a fight with my brother.”

“It’s okay,” the operator says. She sounds calm. “What’s your address? We’ll send someone over to check on you.”

By the time the police arrive, 아빠 is sitting up and I feel even more stupid. They ask him a few questions to make sure he’s all right and pull aside David to ask him some questions too.

I turn to one of the officers. I feel like I have to explain why I dragged them over here when other people with real emergencies need their help.

“Two years ago,” I begin. “My mother.”

The officer looks at me. “I know,” he says. “I’ve been to this house before.”

I feel a little dizzy. I can’t decide if the universe has played a cruel trick or shown me a miracle. Later I will wonder if I made the whole thing up entirely.

A list of things that could be secrets: agents, admirers, Santa, birthday parties, family members, fetishes, massive debt, inherited fortunes, affairs, military bases, settlements, report cards, hole-in-the-wall restaurants, engagement rings, diagnoses, tattoos, marriages, pregnancies. Limited only by imagination, they are not bound by physical restrictions of size or shape. Because they exist in abstractions, anything can be a secret.

All secrets are mysteries, but not all mysteries are secrets. Mystery suggests the unknown, but a secret is defined by the presumption that at least one person knows the answer. Meaning, a secret must belong to someone. Meaning, a secret is a weight fastened around the neck.

Put like this, it’s easy to understand why secrets are so easy to spill. Nobody wants to carry such a heavy thing alone.

Things continue to get worse at home. I find out that David has started selling weed. I don’t tell 아빠. He worries too much already. He works long hours and doesn’t sleep. I remind him to eat vegetables and take his hypertension medication. Both refuse to consider therapy. I almost drop out of graduate school so I can keep an eye on 아빠 and David. It’s true that my friends know what happened to you, and for a while I thought it was enough. But no one in a position to help our family knows the truth. If David acts up, it’s only because he’s grieving; if 아빠 seems paranoid, it’s only because he’s stressed. 아빠 makes a rule and David breaks it. 아빠 says no smoking allowed and David hotboxes in the bathroom. More objects get thrown against walls.

In the end I’m too much of a coward and I run away again. Five hundred miles away, back to Baton Rouge.

It is winter. I am so tired of being cold.

David calls me one night to say he’s been kicked out of the house. This isn’t anything new, so I hang up and call 아빠 instead, who says David hit him with the car, reversed the car and tried to kill him. “Are you okay? Do I need to call someone?” 아빠 keeps repeating, “He tried to kill me, he tried to kill me,” so I figure he’s not in critical condition. I call David back. He’s crying now, saying he knows he’s a fuck-up but doesn’t know why, how did he get to this point? I’m so sorry, I tell him, and he says none of us understand because we weren’t the ones who found you.

아빠 doesn’t listen when I beg him to let David back home. He says David doesn’t love him, which is the same thing David says about him. My father and my brother, more similar than they know, so alike they can’t even recognize it.

“Where will I go?” David asks in a small voice. It is a question I’ve been asking myself. Where are we going to end up after all this?

I send Marian a message asking if she’s free to call sometime during the week. It’s almost three in the morning in Atlanta, and Marian is in her sixties and retired. She should be sleeping but she replies immediately. She admits that she and Nelson have been worried but were afraid to overstep. “Just let me know when you’re ready,” she says.

It’s harder than I thought it would be. I’ve told people the truth of what happened before. My friends know, my professor knows. My classmates know because now I write incessantly about mothers who desire to kill themselves. But this is the first time I will tell someone who held your hand and cried for

you, begged you to come back, and it is so much harder than I thought it would be. “I’m so sorry you’re stuck in the middle of this,” Marian tells me. The connection is bad but I can tell she’s crying. “No matter what, remember how much your mom loved all of you. She just had issues that got to be more than she could handle. It’s no one’s fault.”

Marian is the first adult who isn’t family to tell me this and for some reason, that makes all the difference. Does it still make me a child to think of older people as adults? She tells me that David will always have a place to stay with her and Nelson, and that they’ll both check on 아빠 regularly. “Part of trauma may be keeping the circumstances of Jung-eun’s death a secret,” she says. “That’s a big burden to carry.” I know this, but hearing someone else say it back to me is devastating. “We are on board and ready to help anytime,” Marian says. Then I am crying harder than I have in a long time.

In January, I begin training for a marathon in Atlanta. The first time I registered for one, you died the week before race day. I taped my unused race number above my desk, where it bothered me like a rash. This year, I take nearly a full hour off my personal best. Afterward, I eat six pancakes. Marian is there too. She gives me a hug and tells me that I’m crazy.

I’m writing a book. I thought about making the mother an artist, but it felt too much like I was writing your biography, so I made her a pianist instead. And she does hang herself, except that’s not the end of the story. She writes a letter to her daughter. I haven’t decided if the daughter gets to read it yet.

I’m thinking about what my professor told me: how I’m wandering in tighter and tighter circles looking for you, hoping that maybe one day, I’ll find the center point.

Katherine Yeejin Hur is a Korean American writer from Atlanta, Georgia. Her work has appeared in The Southern Review, Black Warrior Review, Best New Poets, and elsewhere. She is currently at work on her first novel. You can find her on Twitter @_khur_