ON BEAUTY, AKA MANY MANY BALL JARS OF PEONIES DROPPED PORCHSIDE BY RELATIVE STRANGERS

Last night we had dinner with Claire and Mason at the flower farm in Spencer where Mason is cat- and farm-sitting. Being a flower farm, you can imagine that it’s beautiful: hoop houses full of cockscomb the size of your head, a fig tree from which the four of us shared a single ripe fig, fat rows of yellow and orange marigolds, eruptions of feathery ornamental bits—amaranth, sea lavender, rice flowers, sorghum, strawflowers—and of course, being Indiana, zinnias in every color, raspberries, sunflowers, I could go on, and the very names alone might prompt a study of beauty, but that’s not the larger point. What I wanted to tell you was how not only is the flower farm in Spencer really pretty, but equally so is the drive out there, or most of it, once you get past the dreary strip mall and its attendant Shell station on Route 46, whose other name is East Temperance Street.

That Indiana is beautiful seems obvious and surprising to me all at once. Obvious because is there a place on earth with grass and sky, cloud and wind, tree, deer, moon, and meadow that is not beautiful? Is there a place where the sun rises without eliciting astonishment? In early autumn as the light sharpens with imminent death, clarifying all the loss to come, is there an unlovely sight? Even a heap of tires towering beside an eviscerated barn is capable of igniting our awe, drizzling the honey of wonder onto a million questions within: who placed the tires here, one after the other, and over how many years? How were they made? What was their earlier iteration? Who drove the cars to which these tires were once attached? And what stories were told that day with the windows rolled down? Whose hands in whose lap? And see how the skunk grass grows through the donut holes of their centers? Which untold generations of mouse, rabbit, and spider have found shade in the tire’s mouth, its hidden grooves and edges; which critters have sought shelter inside the stinking hill of black rubber? Above even the ugliest and least biodegradable sites, the stars still glisten, winking down at us who dream heavenward, mouths slightly open through the night.

I say surprising because I’ve lived in and hail from decidedly more beautiful—that is, more widely-recognized-as-beautiful, or publicly-agreed-upon-as-beautiful—places. Places that when you mention them in passing, your interlocutor coos approvingly, “Oh, what a pretty place to live” or “I hear it’s so beautiful there.” The rolling hills of Western Mass, black bears sauntering along country roads; Maine’s pristine and dramatic beaches, not to mention Acadia and the salty charm of those small towns down east (up north, for those of you who don’t know); the color-saturated drama and unceasing sunshine of Southern California, the epic and bristling Pacific, those dusty canyons I slept in, the scrubby purple hills lined with rose and hibiscus and agave and eucalyptus; which reminds me too of the grand cedars of Lebanon—by now you’ve heard about the scent of orange blossoms wafting in the air, maybe you have even glimpsed the glittering turquoise and azure sea (the Mediterranean); perhaps you know of the small island about 25 minutes (as the plane flies) west of there, where I was born—to olive and palm and stone and sand as striking and ancient as Sappho’s tongue. The very seat of civilization as many (by which I mean my mom) would say. Did I mention the jacaranda trees, their vivid petals scattered in the streets of Beirut like purple tassels? The pomegranates? The astounding inflorescence of bougainvillea in fuchsia and violet, tumbling down like gigantic, fluffy goddess hair. These are—you are nodding along emphatically now, I’m sure—commonly approved of beautiful sites (and sights!), packed with scenic vistas and observation decks for picnicking and other pleasures.

Most often when Indiana comes up in conversation, no one says, “Oh, lovely” or “Oh, I hear it’s really pretty out there” or “What a beautiful place to live.” In fact, just last week I was reading poetry in Indianapolis at a sweet bookstore called Dream Palace Books, and while chatting with one of the other poets before the event, I explained that we had just moved back to Indiana from the northeast, and without skipping a beat she honked, “WHY?” It always catches

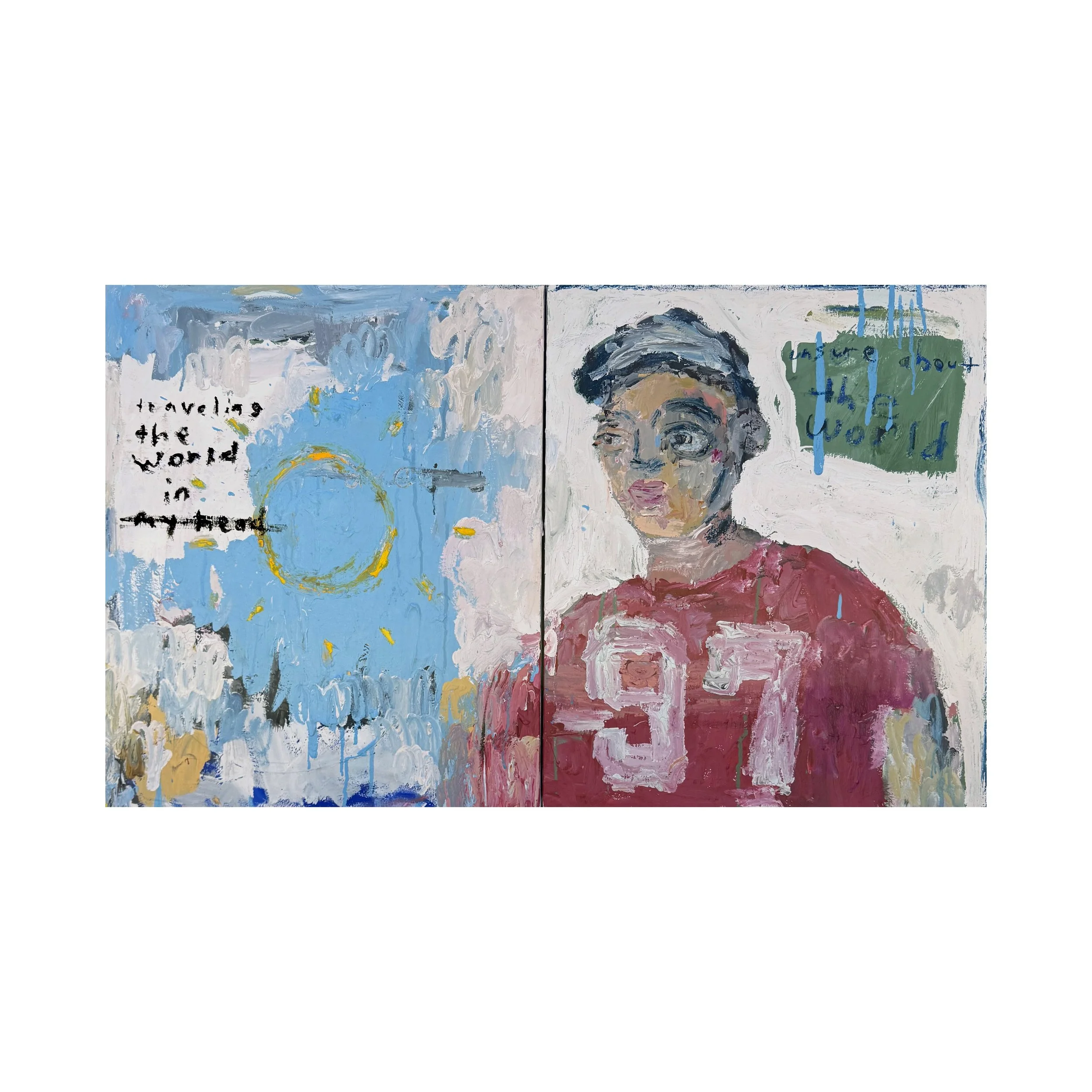

Sun Traveler by Matt Kelley

me by surprise when I encounter such vehement disdain for Indiana, a place and part of the world to which I attach maybe only the tiniest iota of my identity, having lived here for a few years, but to which, in spite of that fact, I owe great debts of gratitude—for something like a deepening sense of what a home could be. For life-altering experiences of community, friendship, and what I often call an economy of care and gift-giving. Think: many many Ball jars of peonies dropped porchside by relative strangers; mounds of persimmons and pawpaws and Concord grapes and Blue Fruit tomatoes deposited carefully by giant angels masquerading as humans on your stoop; a book with a note tucked into the mailbox; invitations to read one’s poems alongside this or that international anarchist collective; a landlord who brings you fresh eggs from her chickens and who your cat moves in with for a year while you are off writing poems many time zones away; friends and former professors who gladly let you store your stuff in their basements; doctoral students in free jazz who welcome you into their band; sycamore trees with leaves the size of a dinner plate; about five farmers markets—long story for another time—and perhaps above all, a staff of especially friendly Hoosier—dare I say, aunties—at the BMV on Curry Pike.

All that said, I tend to believe that such bounty as I have outlined above is in fact omnipresent and not at all limited to the place where I currently reside. I’m not trying to make a case for exceptionalism, especially given the many terrible things in Indiana—no access to abortion, no healthcare for trans kids, the many sundown towns, the 650,000 tons of explosives at Crane manufactured and deployed to murder life, and plenty else. But having moved

more than a dozen times, I’ve developed the hunch that there are wondrous people and portals waiting for us everywhere we may go. It only takes a little extra discipline to see that mutual regard—by which I mean small and enormous acts of love—is too plentiful to count; it’s quite literally happening all the time. Whoever held the door open for you today, whoever said they liked your shoes, whoever asked you for the time, or for directions, or invited you to go with them on a bicycling mission to pick up some galettes. Whoever made you a peach cobbler and left it on your patio table with a small clutch of wildflowers. We go on and on like this: borrowing a ladder, feeding our neighbor’s cat. Sharing a laundry line. My impulse to notice it here is not because it’s exceptional, but because it’s lovely and worth noting as much as we can, given the genocidal offices we are straining against. Just yesterday, I was eavesdropping—pretending to read—on the couch while my housemate and her friend Marie ate bowls of delicious miso soup, which my housemate had made (she’s a terrific cook), and her friend Marie went on for a good five minutes about how happy it makes her to have spontaneous conversations with strangers at the grocery store, on the sidewalk, wherever. She said, “I could cry it makes me so happy,” or something like that. Could be that precisely these moments keep us alive. Crying as we must along the way.

And it’s true that it’s everywhere but it’s also not every where! The last place we lived, we installed a clothesline between two big trees in the sunniest part of our yard—truly a spectacular place for the quasi-spiritual event of drying freshly laundered clothes, sunning pillows and bedding, airing out one’s linen bits, etc. Within a week we were the recipients of a handwritten note tacked to our front door by the owners of the property upon which we resided, who told us that they couldn’t stand the sight of the line we had hung up, though they too loved “air-drying clothes,” and could we please take it down as soon as possible? The property owners insisted that they would purchase for us a Brabantia Rotary Clothesline, which they promised to install behind our house so no one would see it, coincidentally in the darkest part of the yard where

there is nary a ray of sunlight. This was the second incident of duress around a laundry line in that town—the first happened a year prior and was even worse, but I’ll spare you the details.

And in the first weeks of living in that Very Pretty and Pretty Insufferable northeastern town, we were at an event hosted by the institution where I taught at the time, and a colleague, upon discovering where my partner, who is very much from Southern Indiana, was from—all the greats and grands and mamaws and aunts and uncles and siblings and parents and niblings and stepparents still there, within a six- or seven-mile radius of one another—replied with a sneer that only a middle-aged white man named Keith can manage, “I’m sorry,” cracking this joke to my partner’s face and at the expense of his homesickness, which was at the time quite pronounced, my having pulled him along from place to place, away from that one stretch of landlocked land most beloved to him, where he feels so deeply and darkly at home.

And in fact when we plotted our escape from the aforementioned “beautiful” Northeastern town, and especially urgently, our escape from the aforementioned institution (what many others seemed to think of as a “beautiful” job—is there such a thing?), I could just anticipate the wheels of shock turning in my colleagues’ and bosses’ eyes upon learning that we were leaving this arrangement—an arrangement that included, among many other discomfiting things, luxuries such as free and “well-appointed” (read: gigantic) housing with absolutely no clotheslines allowed, to return to ugly old Indiana, neither of us having a fancy job lined up there (neither of us, in fact, having… any…job lined up, at least not one that we knew about, at the time that we were hatching our plan) neither of us rushing off to the next bigger and badder opportunity cushioned with health insurance, or competitive retirement contributions, or professional development funds. Because we wanted to. Because we knew what else, and who else, waited for us there.

—————

janan alexandria is the author of COME FROM (BOA Editions, 2025). Her poem “On Form & Matter” won the 2023 Adrienne Rich Award, and her poem “Open Letter To A Politician” is featured in Lit Hub’s 50 Contemporary Poets on the Best Poems they Read in 2024. janan teaches at Indiana University and in community spaces, edits poetry at The Rumpus, and helps curate Mondays Are Free, a Substack collaboration by BFF poets Ross Gay and Pat Rosal.