Nyssa Cheruvattam, silent

HOW TO HOUSE THE WANTING

There are two ways to do it:

You can assemble a team of quarry workers to drive a gas-powered locomotive over two tracks laid into a vast field of fossilized coral limestone, its surface already etched with ancient worm trails and fern imprints now sprouting young green shoots. Rows of motorized chisels attached to the machine’s base will rise and lower to bore a series of parallel six-inch-deep grooves into the rock, as you continuously pump in saltwater to clear debris. You will then drive the machine back to the beginning to start again, chiseling deeper and deeper through layers of life until the grooves extend ten feet down. You will turn off the machine, reposition the tracks at a right angle, and repeat the process to make a second set of grooves perpendicular to the first. Once you’ve cut a checkerboard into the rock’s surface, you’ll drive in steel wedges to dislodge ten-ton chunks, as if serving slices of a sheet cake. In the event the wedges won’t budge it, you can use dynamite.

Or, you can find one five-foot-tall Latvian man with tuberculosis and a broken heart.

No one knows how he built his coral castle all on his own—with his hand tools, his fourth-grade education, his childhood spent casually or maybe not-so-casually observing his stonemason relatives before migrating to an undeveloped plot of swampland at the mouth of the Florida Everglades.

The leader of our tour compares it to Stonehenge, the Great Pyramids, the Taj Mahal.

The story is she left him back in the old country, his sixteen-year-old child-fiancée, and it broke him so fully that he built this for her. They don’t delve too deeply into her age on this tour—it was 1913, is how they seem to get around it—but it’s easy enough to infer that this man, twenty-six at the time of his abandonment, was a creep.

A creep who quarried and moved multi-ton slabs of coral rock and built himself a home without mortar, using only precise counterbalancing of weight. Rocks joined so seamlessly no light shines through, and a steel rod, retrofitted from a Model T Ford, on whose axis a six-thousand-pound gate revolved at the touch of a hand.

There are enough coral chairs, coral beds, coral bathtubs for an entire family, though the builder lived alone until he died. I recall a dark detail about a repentance corner, a kind of stockade with two openings: one for a wife, one for a child. Most sinister of all: a nearby chair for a five-foot-tall man to sit in judgment.

But the truth is, I’m only half-listening to the details. My attention is fractured, as it always is now, focused partly on making sure my three-year-old daughter doesn’t get restless on this tour. I shouldn’t have bothered: she is silent, riveted, for the entire hour. What she hears stays with her, presses a nautilus into the moldable landscape of her brain. For months afterward, she will, with zero introduction, tell strangers a story they have no context to understand as they bend to hear her small voice on line at the deli, the coffee shop: The man who built the castle was tiny, she’ll begin, before shifting to a dramatic whisper, and his heart was broken.

Most of the time it seems too exhausting to explain what she’s talking about, so I don’t bother. Let them guess.

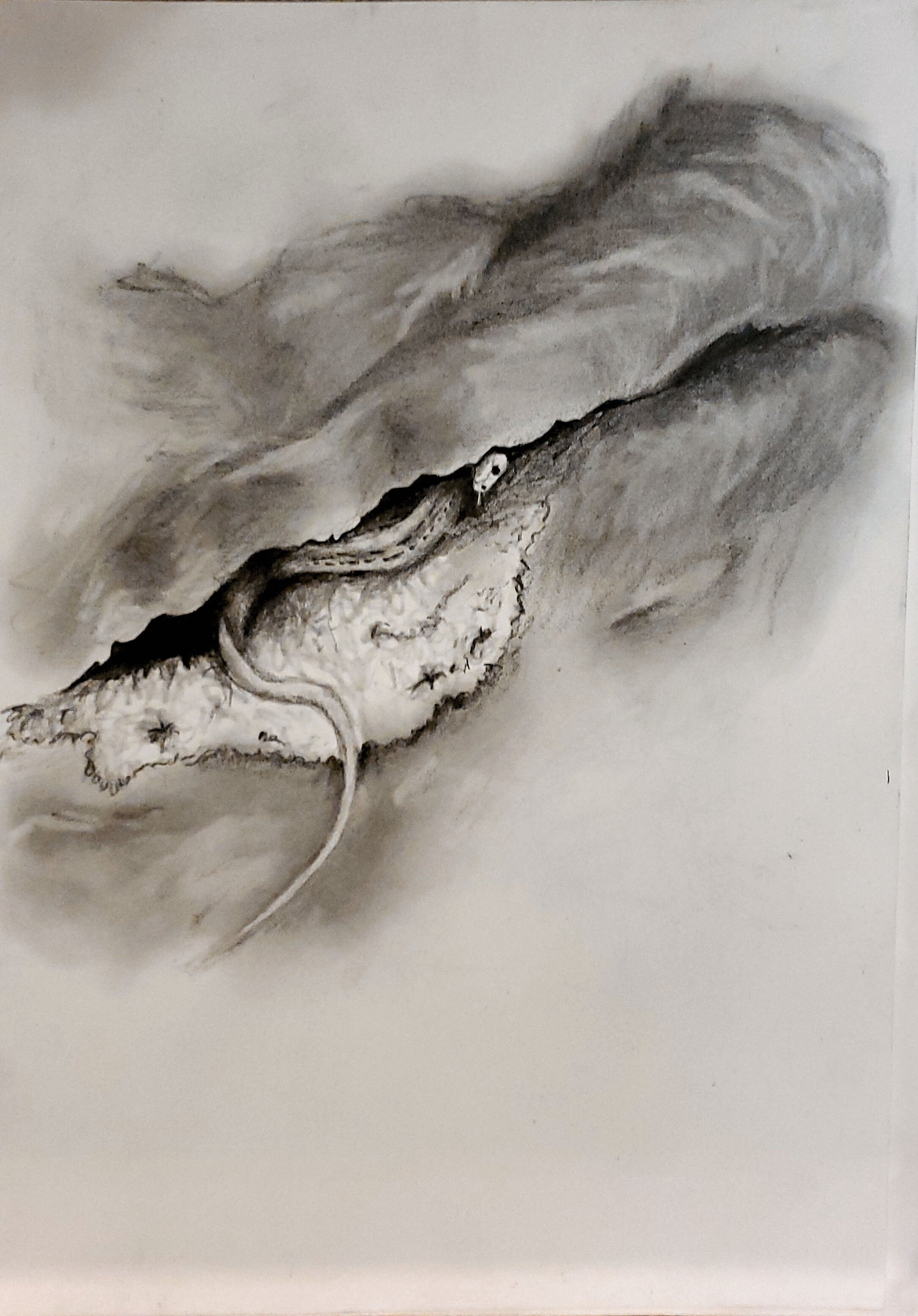

I take a lot of pictures that day, of the loosely-coiled sea life on the coral’s surface that looks like cerebral cortex. As I take them I imagine I’m someone else, someone whose eyes I’ve been wishing I could see through. Someone I encountered once, months before, but haven’t managed to stop wanting. The wanting has taken so many forms: a collection of unsent drafts attempting contact, an entire life I’ve imagined out of internet scraps, a you I think about many times a day without actually knowing you at all. And I’ve wondered, ever since, what it is I even want—what my life wants from me, in making me want you—or whether what I’m really holding onto is the feeling of wanting itself.

The builder, for all his plans—I suspect he didn’t know either. Was it that he couldn’t help it, that he built his castle and wrote his years of unanswered letters to his almost-wife just to blunt the misfiring of his own desire, give it empty air to sail through, and somewhere to land?

Because we don’t build shrines to the ones who breathe beside us: we do it for the people we have to create in their absence, to carve out a space for all the things we’ll never know.

When I revisit the pictures of this trip a year later, my daughter is tiny, a different person. Shaken, I take new pictures of my own face, trying to pinpoint how much I’ve transformed in this time, how many cells replaced, how much blood, whether any of me is the same as it was the day I met you and it felt as if a door swung wide open, a door I barely touched.

And I wish I could be as stone-faced as the ex-fiancée, who never answered a single one of the builder’s letters, and eventually grew into an eighty-year-old woman who finally, after his death, responded to the castle staff’s invitation to visit with something along the lines of I didn’t care then and I don’t care now.

But I know in my gut, in my worm-trailed heart, that if I’m anyone, I’m the builder, the writer, the creep.