You’re fifteen and you’ve never gone anywhere. None of the cities of the world are meant for you, so you carry a junkyard between the pages of your newest journal. Memory scraps picked off the sidewalk, a receipt plucked from the pocket of your grandmother’s jacket. When you lay it on your desk belly-up, there is the grocery store at the corner with 1.99 dollar soda cans, your worn-out shoe laces made into ribbons and shoved into a ziplock bag, an unreturned library copy on the physics of space (100 billion stars in the milky way, says the note), one broken needle held down with blue painter’s tape. You’ve chased the words off the pages. This is THE UNIVERSE. This is everything you will ever have.

Your first love keeps the score in a diary with orange ink. Your name is penned there, in glitter, and next to it is a large three. That’s how many times you beat her in maths this semester. It is as many times as you’ve thought to yourself you want to kiss her. She does not need diaries; she has you and ten other fools for pages. Your pen is a blue ink ballpoint stolen from your mother’s office (she never asked you about it, and you will not tell, she will see you hold it and know this was inevitable). Your teeth do not make good stories, but sometimes they are fit for gossip. It’s about mimicry, the wanting. That’s what you think. Not about a desire to inhabit, but to become. Your first love’s wrist swirls at the end of an S to make a flourish. You bend alongside the curve, watching her write. Then you take it (you will use her slant to write STARS).

When your eyes meet, you find yourself wishing for different shapes. Her fingernail cuts across the narrow slope of your shoulder, testing how far you’ll lean away. You watch her lips press together, as if she is contemplating testing you with those, too. She won’t. You believe you can forget that moment. You pretend to let it go.

*

But this is your universe, and nothing goes. Everything piles up for keepsake. You steal another pen. If she knows it is you, she never says. Like the pen, the color of your summer sunrise is rust, an emberic cigarette cherry, scraped knees, your mother’s tangerine curtains, pill advertisements on TV cafeteria pop can-orange, and you (you and Her and that girl from your history class and her cousin and your friend’s classmate with black hair and chipped teeth and the girl from that band you saw in someone’s basement) kick your feet up on a bench with your backs on the street pavement. You should be wearing sunscreen. Your mother used to wipe it over your face until you cried.

You melt in the warmth and the first girl you ever loved asks, What’s dying like, you think? And you turn your head to the side to face all of them. They all have the same eyes: eyes that could want you back. Your arms press together there, on the ground. Sweat curls the hair at the nape of your neck. Maybe it’s like swapping clothes. Math class girl blows a strawberry pink bubble with her gum. One of you giggles. It’s like leaving and never coming home. Someone sighs into the air. It’s like being forgotten.

It’s probably you.

You imagine the scalding ground burning through your T-shirt and kissing your back like it has swept red across your cheeks and nose. Your blistering summer is coming to an end. When you rise to leave, peeling yourself off the pavement like the used gum smeared next to math girl’s head, you stop yourself from taking it with you. Even though it’s so perfect for this moment. For the remembering. The wanting-to-keep. Instead, you take a dandelion from the ditch and pinch it between two pages, its grease smeared across the paper like a shadow.

*

Your mother keeps diaries from your grandmother and half of them are about sacrifices. You worry about having nothing profound to say in your own. You do not keep your sacrifices in a journal; they’re built into your future. When your daughter (who is spoken into existence before you are half a person; who is spoken into existence when you are; who others will grieve the idea of) pries your boxes open, can she imagine you on the pavement, T-shirt dirty from the ground, full of disbelief? You don’t want her, but she already exists. You will dream of her even if she never comes to be.

You don’t tell anyone that maybe staying where you are is what love is really like. And that, if it is, you don’t want to love anyone else ever again. In your universe, all your birthdays have been spent in the same room, with the same birthday cake, the same candles. Your mother has tapes of it. Sometimes she watches them without you, and you consider asking her if she dreamt of you before you were, too. Who she left behind to be your mother. What her name looked like in someone else’s diary.

It would be easy to pull the worn-white lace tablecloth over your head in surrender instead of reaching for the kitchen knives. But it is all edges with the both of you. Even in the mirror, you see her. And in the hoarding. She is there, too. In all the pieces you have put into your journals, wordlessly wishing to be a little different from her. After all, she knows what surrender looks like. And you don’t want to believe that you can, too. Not quite yet.

You imagine this: your mother looking at you, at the lace covering your eyes. Using your name, only to realize it didn’t fit in the room. She pushes the furniture aside. She reaches for you. She tries to lift the veil.

And when none of it works, she holds you.

And then she lets you leave.

*

All of you and your friends are shoved into the booth of the breakfast place like the fermented herrings from the tins in your grandma’s kitchen. None of you have much money, but you split five plates of waffles and drink coffee because you think you’re adults and adults: know things, drink coffee, talk about the world but you don’t know anything about the world, so you talk about the old lady’s cats, who kissed in the hallway yesterday, the family who left for the city. You’re the one who says, Maybe I will leave, too, someday, and it’s everyone else who laughs. They don’t know about the haunting occurring in your childhood home. About the girl-like mirror image following you between rooms, trying to make you look at her with your mother’s voice and your grandmother’s cardamom scent. There must be a difference between fleeing and leaving. You don’t want to believe you will lose anything.

*

There is a gas station, and you sit on the curb watching the beat-up cars fill up on fuel, wondering what would happen if they put diesel in on accident; if the ignition, the thumb-sized-lighter-tongue, the flame, if everything you know would extinguish itself, if you’d see a fire. Would the sky and the buildings and something dry like the grass fields ten miles to your right finally have some spark?

There are no streetlamps outside your house—that’s why she insists on walking you home. You pretend to be worried, so that her damp palm can cling to yours. Both of you look up and there are stars, one hundred billion gas stations burning up. You start counting them.

The girl you love says your name. It catches on fire along her teeth. It becomes soot on your shoes, the ones you picked out together. She kisses the last of it off, so that there’s not too much left of you to grieve.

You know you should live these seconds out, but they’re lost the moment you imagine what your life will be like when they’ve fizzled out. You excavate the last bit of yourself from the pavement you melted onto like soft lipstick. Maybe she’s written about you in her diary. That she stole something back from you, so that you’re never really gone. You hope she used orange ink.

—————

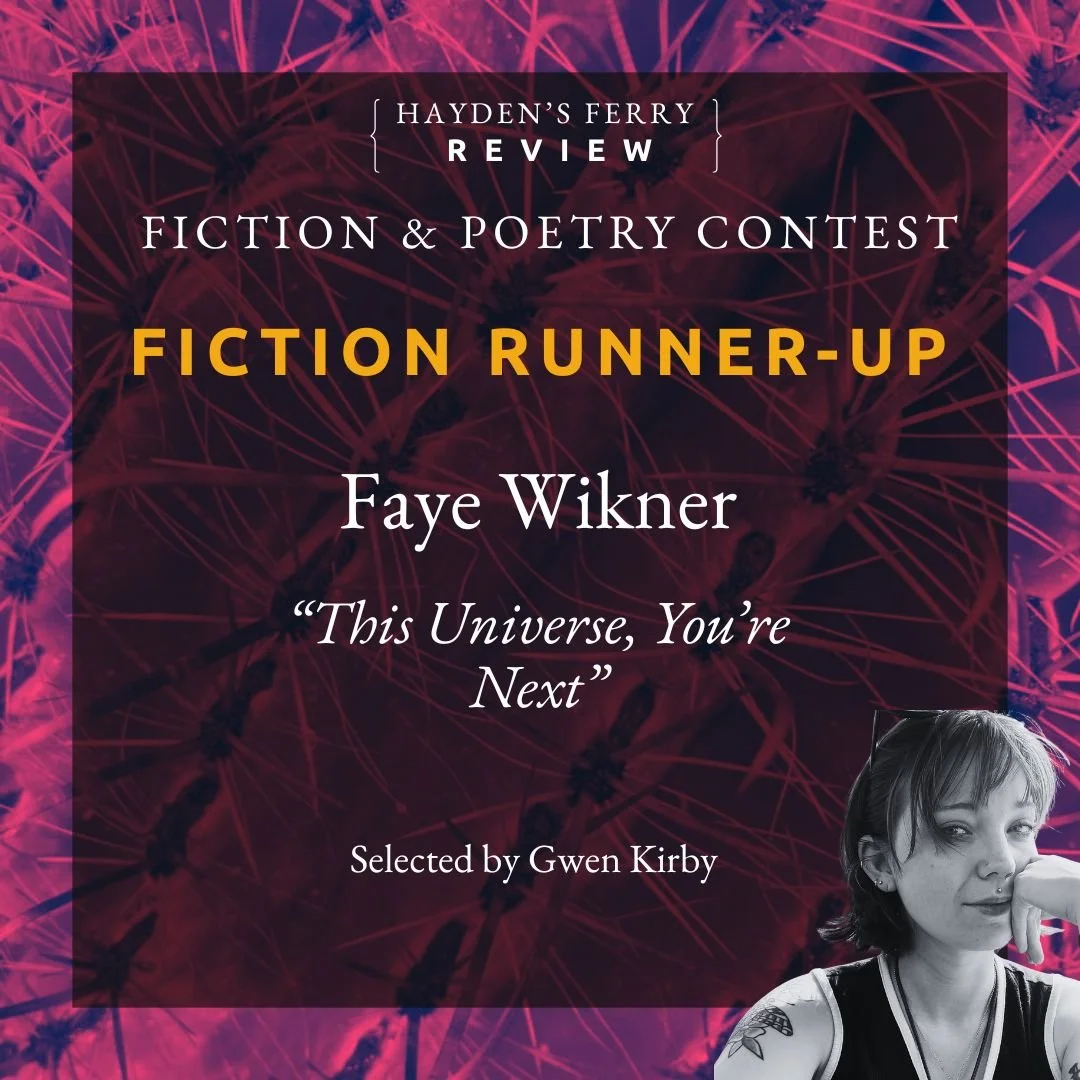

Faye Wikner (she/they) was born and raised in the lingonberry forests of Sweden and now resides in New Jersey with her cat. She received her MFA from William Paterson University, where she teaches intro to creative writing. She is the associate editor of Map Literary and reads prose for The Adroit Journal, and her work has been published in CRAFT Literary, The Colored Lens, Short Beasts, and elsewhere. She was the runner-up for Feign Lit’s 2025 Reign Prize