Susan Solomon, Macaw

Hands

Today my mother’s words

sound final. And perhaps this is her first true thing.

Her hands have not been her hands…

–Safiya Sinclair, “Hands”

Her mother had not called the law, yet they had appeared with their long hands like a lizard and snagged her, hands that spun and stretched in each direction and preyed. Hands turning up at their own front door to cuff her mother’s and proceed outside. They wanted just to ask her mother about her partner, they’d said when Sabra and her sister Foïla had visited the police station with their play aunt. Talking at their station would be a better look for her mother, they’d said as they processed her mother’s personals: the nice clothes her mother wore only for important social affairs, her stud earrings, her phone. Fingerprints. So Sabra knew the state’s sneaky ways. She knew they were underhanded.

Today the state was giving instead of taking. Their teacher kept licking her lips while she announced that for the first time a student in their class would be joining the mathletes. The math bowl would be on television, she was telling them, and they could watch it even without cable. The school held a C grade in Dade County and this year wanted to show out with all their best aces, their crème de la crème…the whole time the teacher mouthed off she licked and bit her lips. It tickled Sabra to witness, so much so that she found herself nudging Danielle, her desk partner posted on her right, to tell her that the teacher was eating herself. She could just as well have been a cat or a frog acting like that, just snacking on her skin. Sabra looked to her partner to say this, and Danielle was using one of her mechanical pencils to poke a boy on the floor in front of her.

The rest of the class was out of their seats and some on the floor clutching giant protractors, looking for acute angles in the classroom. Some kids stood huddled in corners. Some kneeled like pets. Except Sabra and Danielle, who sat near the back graphing even and odd functions. The functions shot up the gridlines, curving like kickballs in a way that pleased Sabra. She had already learned all the ways angles bent her world last year, when her big sister Foïla shared her geometry homework with her, when their mother could make her share.

Their teacher began to float around the room like seaweed in her tight green dress, and then she was at Sabra’s desk as Sabra was looking for the point where the graph would turn around. When her teacher squatted, her long gold necklace clattered on top.

“If you’d still like to join,” her teacher whispered. Sabra would still need to ask her guardian for permission, but she would now be a late addition to the mathletes, the team’s only third grader. They needed her to make a splash grand enough to flood the district, the regionals, even the state. Her grades had proved she was capable, her teacher hissed. Up close, her lips looked blistered and tender. Sabra stared at the pinkening fingers pressing down her book, the blood being forced front.

“Just as an alternate, you see,” her teacher continued. “Who knows what you could achieve.” She placed her hands facedown on Sabra’s math book. “Would it be too much for you?” she asked.

“No,” Sabra whispered back. It was almost as much as she could hope for. She bent her head to her book, which wasn’t the same one the other kids used, which tossed out tougher functions to map out, resettle. She felt herself begin to get big. A new thing boiled in her chest, No, heaping bubbles of No. When the teacher streamed off, she turned to her right and her partner was smiling at her without showing her metal teeth. Like she had trapped something in her mouth that was trying to escape her. Her eyes were trained on Sabra’s shoulder, and Sabra looked down on a long slender braid trailing out of her ponytail. She grasped it to tuck it back in and found that the whole braid had unlatched.

Danielle giggled. The braid curled in Sabra’s hand like a helpless snake, looking silly. Mingled in its rounded tip were short strands of darker, frizzier hair that she recognized as her own. Another loose braid. Another that had once supported her, had once held as tight as vines onto her head when her mother had traced them in so long ago, and Sabra’s head had flamed for ages and ages after, she had slept on her side for ages and had tried not to roll on her back so as to tug on the braids anymore. Now they were dropping out one after another without her notice. She heard the quiet laughter and it was like a monster huffed in her face.

“Here,” one of the girls behind her said, tapping her back. Sabra turned around, just as the girl was passing what looked like another braid—another braid!—to her desk partner. When Sabra reached out her hand the girl passed it to Sabra’s partner, who sat back and fingered it. “You dropped this one too,” Danielle said.

“I didn’t drop it.” She tried to keep her voice low.

“The hair’s so soft,” Danielle replied.

“That’s ’cause it’s hair.” Sabra reached for it, but Danielle angled away.

“How much did they cost?” She held the braid around the middle between thin fingers like it was alive. She stroked the ends.

Sabra reached across quick and snatched it before her teacher could see. She bundled the two braids together and clutched them in her lap. Through the gaps in her hands they peeked out, jeering. She whispered, but not too quiet so the monster could hear, “Cost more than your whole family ever make.”

“We didn’t think it’d feel so soft,” said the girl behind her, sounding almost unbearably nice. Sabra didn’t want to feel nice with her words. The teacher clapped for lunch and they all scrambled up, slamming books shut, returning desk chairs to their right places, stacking the protractors on the teacher’s desk.

Then in the noise Sabra’s head was yanked back. The pain that followed slapped. “Ahh!” she said loudly for someone to mind her. She cupped the back of her head and turned around and around again as the kids moved to line up at the front door. “Ayy!” she said loudly again.

When she got in line, she noticed the girl turned back from two heads ahead. The face of her glasses held bright squares of light that blocked her eyes. She stepped out of the line and held out her hand.

“It just fell out,” the girl said. Some of the other kids turned to gape at them. Sabra didn’t take it. Then the girl tossed it underhand like a softball. The braid sighed to the floor just as Sabra seized it up, her face burning.

They trooped past the stray cats who were always wandering around on school grounds like the pseudo-couples in Sabra’s class, past the great squirrels tracking the fields and scurrying up the trees. Once they reached the cafeteria Sabra waved for the teacher’s attention. “I left my lunch money. Can I go back and get it?”

Her teacher offered to pay for her this time. Kids couldn’t be in the hallway without a teacher or a hall pass.

“Thank you, but I’m not supposed to take stuff like that.” If her mother heard that Sabra took the money she would ask Sabra when did she begin acting so helpless to white folks and the question would pain her worse than any grounding.

The teacher pouted and squinted at her a long moment. “Are you positive you don’t have your money on you?” Sabra pulled out the pockets of her uniform skort to demonstrate. I’ll be quick, she said. In the corner of her eye, Danielle who could have been her friend was watching her like Sabra was about to tell on her dumb self. Sabra was better than her. She was one of the best.

Once inside the classroom, she scouted the back of her head. She found two free spots near the nape of her neck, bushy with tangled curls, like yards unsettled and full of weeds. The feel of her hair calmed her. With her fingers she rooted through the surface of her hair until she found the spot for the third braid, the one they had pulled out. It was free of anything. The small square of scalp felt soft and slightly bumpy and moist where the skin opened up. When she looked at her finger tiny blood drops pebbled the skin. At the sight of them, her face began burning again, but she took another deep breath and sat down and for the moment did not know what to do.

Since when were you so helpless, her mother asked in her head in an almighty voice. Hands on her hips, free of their cuffs, she stared down at Sabra. Her voice sounded different than it had in real life, engorged and trembling.

Sabra sat and thought. Then she lifted the top of her desk and took out a blank index card with her clean hand. She touched the bloody spot again, then rubbed the tips of her middle finger and thumb together and pressed them onto the card. The thin red prints swirled like tiny hurricanes.

On the desk beside her, Sabra opened Danielle’s pencil box and took out all her fancy pencils and one by one broke them in half. Dummy Danielle had too many nice pencils for just her. She put the broken pieces back in the box, she placed her calling card on top. She turned to the desk behind her. Once Sabra correctly guessed the strength for the first pencil the rest of them broke easily, like the grass-blades in her mother’s yard, back when it was her yard.

Susanna Herrmann, House in the Woods

*

It had been hard enough to work up her heart to ask her mother for the things she craved. Now in her mother’s absent place lived a feeling like a pulled muscle, that any want was overmuch, that, when presented, each would float forever out of her play aunt’s reach. After her mother’s conviction, whenever Sabra caught herself craving the new Pumas her classmates bought, or new dolls to replace Bow and Burn, she first tried to test herself out of her wish. That night, as her sister and play cousin slept, she went down to the cooler basement—she had never lived in a house with stairs—a large room her play aunt had organized into a shelter for the discarded: dust-coated treadmill; framed, yellow-tinged family photographs; large cardboard boxes half-filled with canned foods and her play cousin’s old clothes to pass off to Haiti; a painting of The Last Supper that her play aunt had banished downstairs soon after Sabra and Foïla had moved in, when she noted that the black man sitting to the right of her black Jesus was in fact a woman. Sabra pushed the door almost closed and sat on the exercise bike with the broken tension knob and spun and spun and then lifted her feet and watched the blurring pedals. She rocked and panted through her mouth and waited for them to whirl themselves out of agitation. Once they stilled, she began to spin again. While she pumped her legs, she asked herself out loud for the point of gaining what she craved. She tried to weigh her desire.

A small green mathletes polo shirt was not too much. And maybe get her hair redone. Not much. The shirt would come stamped with the school logo too. It would look all official for her mother to see through the TV. Maybe it would be the kind of shirt that came with the pocket. Maybe she could get two. No—could she? The other one maybe in medium? What if she got too sweaty in one? Or in case one size didn’t fit all of her. Maybe she could send the second one to her mother.

When Sabra got off the bike and started back up the stairs, she heard footsteps descending and a voice that stopped her heart. “What do you think you’re doing still up?”

“Nothing,” she said. “I was just looking around.” Her sister and play cousin wore baseball caps and bulging sports bags. Her cousin stood a few steps above, but her sister kept walking until she was a hand’s length from Sabra. “I’m not doing nothing,” she said.

“Let her alone,” her play cousin said.

“Where are you going?” Sabra asked, though she already knew. She had seen the spray cans. She wanted Foïla to admit that she was tagging walls. Then the front door eased open into darkness like a warm mouth.

“Going out to play ball,” her play cousin said, but Sabra was still looking at her sister.

“It’s for high schoolers only,” Foïla added. “You must be this old to join.”

“We’ll be back soon.” Her play cousin stepped closer. “Try to be quiet on the steps. You know they gotta work early.” She tugged one of Sabra’s braids and Sabra stepped back, away from them. “Okay then,” said her play cousin.

“She’s so damn spoiled…” and they had slid out of the house. Before the door had closed Sabra had caught a gush of night-breath as heated as the day’s.

*

“Math bowl. Is that something for struggling students?” her play uncle asked the next day. He clapped over the table, then looked down to inspect his hands. “I got nothing,” he said, his voice dipping into a smoother, funnier deep, like the sound his desk chair made while he worked in it, rumbling along the wooden floor.

Foïla clapped before she could answer. “It’s just a math game,” she said. Soon after they had moved in, the air conditioner had coughed and choked into another broken thing. In the heat of the simmering bread soup, flies feasted. Her sister wiped the crushed fly parts onto her napkin. “Just a game their school makes a big deal about.”

Sabra shook her head. “It’s not just a game.” She tried to think of something big. “It’s really important. Like the Olympics.” She added, “Everyone from all over comes to play.”

“Look at you,” her play uncle said. “A little genius. We’ve got a scientist on our hands.”

“Only the best get chosen,” Sabra said. It had been easy, so much easier to get. Easier than the time her mother went up to the office with her at the end of the bell and demanded they take her out of ESOL. The principal had said that all immigrant children, not just Haitians, were required to take ESOL, and her mother had replied, “Test her,” and for a month the assistant principal had sat in the back of Sabra’s classroom, taking notes. She had made sure to raise her hand for every question, even the ones she didn’t know. Then she was placed back in PE with the rest of her class, when Danielle had asked if Sabra was going to show off in their free time too.

Her sister said, “Is that really what you think?”

“I won’t have time to take you,” her play aunt said. She was stirring more bread into a big pot on the stove, a spray bottle in her other hand. Every so often, she stepped back and squirted water on her face in the way the puffed people in old movies sprayed perfume.

“We’re riding in a separate bus. I just need the shirt. And I need something for lunch. Please.” Sabra changed her voice. “I would like one shirt if I can.”

Her play uncle said of course she needed the shirt and her auntie who was not her auntie asked, “Where is your shirt money?” Her voice almost sounded like she was joking. “You got mathletes money I don’t know about?”

When Sabra had asked for anything, her mother would sometimes wear a look as if Sabra was asking for the heavens. Then tell her that impossible was nothing, like the sneaker ad. Or her mother would say no, that any money was for Sabra’s college and college was a pricey place, almost the most pricey in the world, but she would not look hard then. She would hitch up the corners of Sabra’s mouth until Sabra could smile on her own. Her rough fingers, metal-cold, would cradle the back of Sabra’s head, and her mother would lick her thumbs and resmooth Sabra’s edges, which were always squirming out of their gelled swirls.

Her play uncle turned to her. “I’ll take care of it for you,” and she thanked him and added, to prove herself, “I’m gonna be on TV too.” “You see this?” her uncle asked her play aunt.

“That’s cool,” said her play cousin, and her play aunt said, “I can see I’m outnumbered.” She stopped stirring and slammed her hand on the counter and wiped it with a dishrag next to the stove. Then she looked at Sabra, who smiled and thanked her and felt that she needed to say something more but couldn’t think what. “Maybe we could get someone to redo your hair,” her auntie said.

“Mommy always does my hair,” Sabra whispered. When she had finished her bike ride, she had unbraided the fallen strands and tried refixing them to her hair, but she didn’t have her mother’s hands. Sabra’s fingers had shaken and the long strands kept retangling at the ends.

Her auntie sprayed her face. “What was that?”

“Mom was dead wrong for that,” Foïla spoke loud. “You’re not supposed to be putting that heavy hair on a child. Right, Auntie?”

“You used to get them too,” Sabra said.

“No, I didn’t,” her sister said.

“Yes, you did. Yes, you did,” Sabra shouted.

Foïla yelled above her. “Look how nasty they are, on account of you wanted to leave them in. They’re probably making you bald now. Probably smell like ass.”

“Don’t bring that speech in here,” her auntie said.

All night Sabra had tried to ignore the tingling spot, had tried not to imagine her brain leaking out. Braindrops, her mother used to say, like the time Sabra and Foïla tried to see who knew the most numbers in pi. Let me catch some of your braindrops.

“What about you, FoFo?” her uncle asked. “You gonna join this athletes too?”

Her sister shrugged, waving her hand over her soup. “Can I ask something?” she said. “Do you think, if they could put drugs in a spray bottle like that,” she pointed at her auntie, “you could still get high?”

Her cousin burst out laughing. “Girl, you stupid.” She was a year older than her and learning to drive and was so tall she sat at the table with her legs wide open like a man.

Her uncle frowned at her, scratched his beard. “I don’t know what you mean.”

Her auntie said, “Don’t be disrespectful.”

“I just mean,” Foïla put down her spoon, “if you have pores in your skin, right? And you absorb things through the skin—”

“Girl, would you stop.” Her cousin pushed her chair back. “I’m telling you it won’t work.”

“You don’t know that. Technically, it could work. Scientifically. If you just look at the terms. Right?” She turned to Sabra and raised her eyebrows. “Right, little genius?”

Sabra didn’t reply. She reminded herself that she was bigger than her sister, even though this year Foïla had grown so big she seemed to sprout hair in every place like a wolf. Who in her bigness had lately started to say “her” and “she” in place of “Mommy.” Who more and more lately called Sabra spoiled and rotten.

No one answered. Then her sister said, “Fine.” Held up her hands. “Okay. I was just saying it could be an untapped market, is all.”

“Nobody was wondering,” her play aunt replied.

*

Sabra gave the back of her hand for a mathletics stamp before the team leader led them to a mammoth theater. A million other-colored uniforms, polos of pink, orange, green, all writhing in the mathmaster’s chant, dizzied her in a good way. She looked up into darkness and imagined that the TV cameras nestled there. Her mother could

be watching her from her room in prison, because it would be the type of prison that would have a TV, and maybe her mother would be so proud she would not notice the pointy bun on top of Sabra’s head, pulling up her skin like a giant clothespin. That morning her play aunt had declared that Sabra’s bun was too messy and loose and had quickly, roughly, rewrapped the braids into this high cone-bun in two seconds, pulling the braids tighter than her mother ever had. Each time Sabra blinked the hairs yanked back on her skin like they were in a tug-of-war.

As the crowd roared and waved and changed shape, she stayed seated. So much noise. The ink trails on the back of her hand had purpled her skin. She traced the circular logo. Traced the tildes her knucklebones exposed. Her home directory. On the good days her mother, waiting for them at the front door when school was over, would fist-bump Sabra and Foïla and once their fists connected her mother’s wouldn’t immediately move away. Her knuckles would rock and bump against Sabra’s until they settled into the grooves in her hands.

Her seat rocked with the students’ jumps. She breathed through the pain in her head. After today her mother would see her. Then the chants ended and they all began to scatter like dust, quickly.

She turned to the group leader. “Miss,” she called down her row. The leader barely glanced up as she handed out small sheets of paper to each of her teammates, who upon receiving the sheet turned without a word and hustled off to their trials.

“Excuse me,” Sabra said. “Miss, where do I go?”

“Last name, dear,” the leader said. “Let me see—the alternate, right?” Then the leader shook her head and said, “You’re just going to stay in here for now, sweetie.”

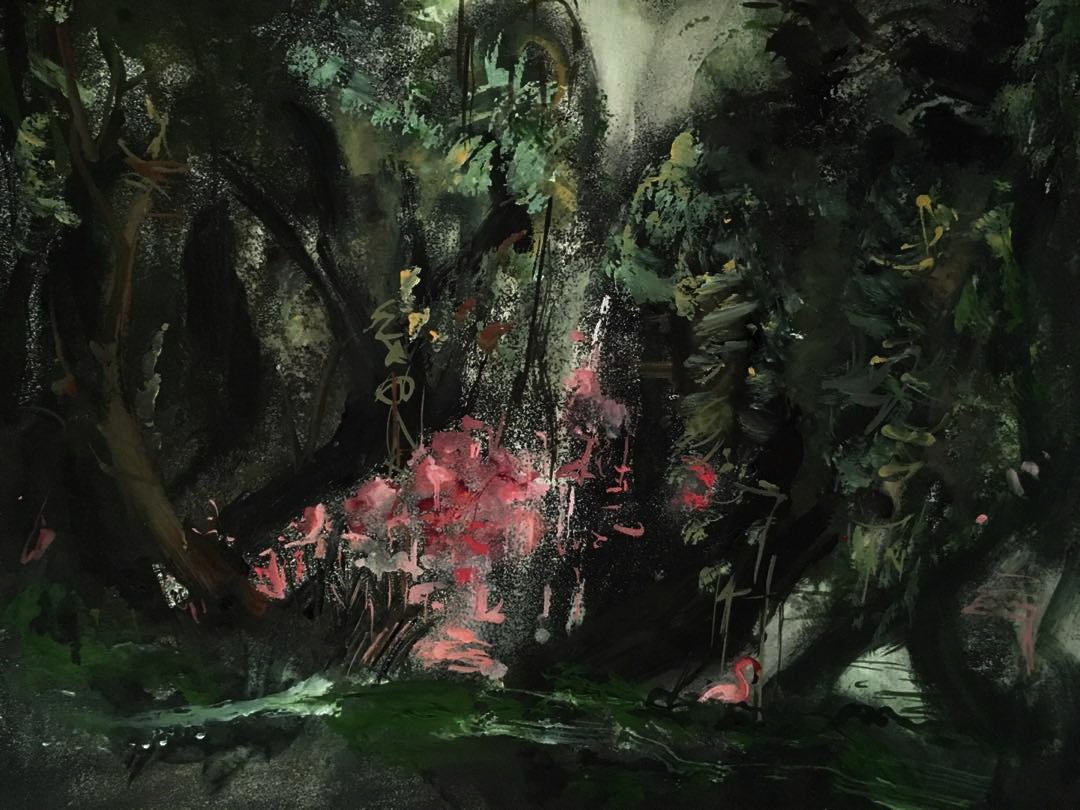

Susan Solomon, Arrival: Flamingos

“What do you mean?”

“Everyone is present.” The leader scrolled down her clipboard again with her pen. “Since everyone is here, you don’t have to compete.”

“But—” Why hadn’t she considered that? Why hadn’t she counted the members on the team to see if everyone was here? Come to think of it—she realized she didn’t even know how many could be on the team.

“It won’t take us long,” said the leader, rubbing her ear, looking toward the stage. “You can wait for us here. You could get some work done. Check out the stage.”

“What if I want to go?”

“What was that, dear?”

She tried to catch the right words. “Can I go anyway?”

The black part of the leader’s eyes widened like a cat’s. “You want to go home, you mean?”

Sabra shook her head. “I mean, can I try out the mathletics test?” She hoped the cameras weren’t catching her now, begging the leader.

“Mm-mm.” She shook her head again.

Then there were three left behind, Sabra and two other students, small twitchy boys from another school, who had their heads bent to something in their laps. Why had she let herself believe without thinking about what it really meant? Suddenly one of them shoved the other and hopped up from his seat. He did not get far before he was pushed from behind, falling onto the carpeted floor. The one who fell cried out in a joyous way, like he’d dreamed of getting pushed, and his voice bouncing around the empty theater was louder than the silence of deep absence, louder than the ocean that had swallowed Sabra, with water that never ended. The morning her mother had taken them she had cooked them thick cinnamon waffles with as much syrup as their plates could hold without spilling over the edges. And walked out to a big-wheeled car and that man—father, business partner, both?—asking them who wanted to sit in front, and Sabra’s hand had flown up before she really saw who she was raising to.

They drove until the chain-linked fences ran out of steam, then he said, “Look at me.” He was rolling the window down with one hand and adjusting the radio with the other. His knobby knees clamped on opposite sides of the steering wheel.

From the back Foïla laughed and clapped. Her mother said, “Chill.”

“Don’t worry about us,” he said. “You the one asked to come.”

“Look at this,” the man said. He raised his arms like he was about to raise the ceiling. “No hands.” Foïla was singing with their Mya. The car bobbing around them.

This kind of beach let them park on the sand. She hadn’t known such a kind existed. The sun not very warm but bright-bright, bouncing off every shiny face, and when Sabra stood on the flat part of the shore she saw she had two shadows. The one in front of her waved and the one behind her was leaning all the way to the side

like she was drunk on light. Sabra walked with them into the ocean. When she bent to the water, the skin on her fingertips shriveled. She walked farther and different waves kept trying to push her back, tip her over left, tip her to the right, pull her forward more, like she was on one end of a straw and someone on the other end was sucking her in.

“What’s wrong?” her sister called out.

“Nothing,” said Sabra. Then a wave made her wobble so hard she screamed and almost fell.

Her sister laughed. “You’re fine, just keep walking.” She called out. “Don’t be pussy.”

She turned back to her mother and partner talking with new people, strangers she didn’t recognize, exchanging bags and shaking heads. But the water tugged on her, though she had to use all her own force to stay standing so she could watch the waves roll one after the other like a game of duck-duck-goose that never seemed to end, duck-duck-duck-duck all the way back to that pale line where the water touched the sky, that kept moving the farther she swam from shore, so that even though bits of voices called on her to be careful, and a rough hand had soon grabbed her leg and forced her around, she had always felt she hadn’t gone deep enough, that she could have gone further still if that line kept scooching back, the sounds of the water beating her louder than her heartbeat drumming in her ears.

Sabra knew she had to let the wave take her where it wanted, no, where it needed her to be. To make her mother see her abilities and feel proud. The word “prison” sounded scarier than the image she conjured, a place that felt happy and light because her mother, scowling and all, was there to take on the bad. And when she saw Sabra up on the TV somewhere in prison, her mother’s happiness would balloon and lift her up.

*

The sun had splintered by the time Sabra rushed outside. Slivers of pale light streaked the gray sky and puddled the school grounds, so big and wide. So full of kids and grown-ups weaving around and crossing one another, how they inched their way across the fields. A low hum of activity seemed to sit on them, like the sound of rushing cars in the distance, yet at the same time no one spoke, no one laughed. They reminded her of the silent looping rainbows that appeared low in the sky, close enough to touch. For a moment she stood in the shadow of the theater and watched.

The sun had splintered by the time Sabra rushed outside. Slivers of pale light streaked the gray sky and puddled the school grounds, so big and wide. So full of kids and grown-ups weaving around and crossing one another, how they inched their way across the fields. A low hum of activity seemed to sit on them, like the sound of rushing cars in the distance, yet at the same time no one spoke, no one laughed. They reminded her of the silent looping rainbows that appeared low in the sky, close enough to touch. For a moment she stood in the shadow of the theater and watched.

She marched with them into a classroom and stood with them near the whiteboard. The leader in here had a clipboard out too. What was this mania with taking names? Sabra smiled but not too wide so that she looked like she belonged there. What was this thing with checking and rechecking them in the place they were already allowed to enter? Hoping no one noticed, she reached in the back of her head and parted her braids and touched the bald spot. It was tingling. When she had checked it after her shower that morning, it had been warm and soft like fruitmeat. Now her fingers met something rough and crusty, like the spot was covered in scales.

“Did I miss anyone?” the leader called.

Sabra raised her hand, telling herself not to shake. She said her last name. As the leader peered down, Sabra said, “I think they forgot to add my name? My teacher said this was the room I had to go to.”

“What school?” She gave her school name. Then she heard: “Go ahead and take a seat on that side of the room.” She chose a seat by one of the windows where red-pink zinnias huddled beneath it. On the other side of the room, she noticed one of her teammates for the first time, a girl in the same shirt who was looking back at her and filing her thumbnail with her teeth. Sabra wiggled her fingers. The girl shifted to another finger. She bobbed her head back.

The volume of a cube is 216 inches. The area of the base of the cube is 36 square inches. What are the dimensions of the cube in feet?

Sabra drew a rectangle on her piece of scrap paper, then shorter lines slanted right from each point. One, two, three, four. Drew dotted lines inside the prism to make it see-through. She imagined the cube was the room, the biggest classroom she had ever sat in. Were all high school rooms this big, with so many never-ending rows of blue desks? They flowed back like the ever-coming waves at the beach. She suddenly had an image of the classroom filled with salty water and she sucked in her cheeks, her mouth prickling.

What is the positive square root of (√48- √45)?

This was too easy to solve. Some things she had no choice but to memorize. Twelve inches was always one foot. The letter m was always the slope. In a word problem, the word “is” always meant “equals.” And things that equal make perfect completions and make no room for remainders except when they didn’t complete. She began to work out the problem quickly, then she forgot the next step. What was the next step? Outside, the air was growing bright and security people and people in studded baseball caps strolled on the paths. She noticed that one of the capped people was holding up a three-legged camera, but Sabra found she couldn’t get excited for it. Not yet. She looked back down for a long moment and tried to call back the formula.

You’ll come back, she told herself.

Find the number pair/group which is different from others.

(A) 12 – 72 (B) 24 – 48

(C) 60 – 74 (D) 84 – 96

(E) None of these

Her mother had been forty-eight the last night they had all slept in the old house, when Sabra had heard someone slam a door. Something her mother never allowed Sabra or her sister to do more than once whenever they played— Stop slamming doors in my house!—her slingshot voice always checking their steps and breaths. But that night someone slammed in. Sabra waited a breath, then sat up in bed. Their wilting white dresser at the foot of her bed looked polished in the beams of the streetlights flooding their room. How many faces did it have? She pointed at each one: One two three four five six. The dresser’s faces glowed. Let’s see how many edges. She traced them in the marshy air. It was like she was drawing on the foggy shower glass, each line wiping away the blur. When she had lined up all the edges she got out of bed and touched each vertex. Now add them all up—but she couldn’t remember if she had counted each drawer separately or not. She rearranged Bo and Burn to sit straight and touched the top of the dresser, wishing it could be cooler for them. She couldn’t come up with another problem and walked to the kitchen. The front door was wide open and her mother was sitting at the table with her head thrown back, her braids trailing over the chair like webs undid. All the lights blazed. Sabra went to close the door and her mother said, Leave that, it’s broken. Come here. Sounding soft, no shot peeking out of her throat. Sabra pulled out the other chair but her mother took her arm and drew her close and picked her up into her lap. Sabra laid back, but her mother said, No, no. She shifted so that almost all of Sabra’s weight rested on her arm, which made Sabra feel like she could break her. That’s not better,

Mommy. For a moment her mother didn’t respond, only shifted more. She murmured, Don’t fall asleep yet. I didn’t like the way you and your sister were fighting yesterday, baby. You should be nicer to each other. She was the one who pushed me, said Sabra. Doesn’t matter. You have to forget it when she does stuff like that. She always starts it. I don’t care, her mother said in a harder voice. You need to be the better one. She needs to be better and you need to be better. So everyone will say good things about you. Don’t you want that? Sabra was hoisted up and off her mother’s lap. She stood somehow. You think you don’t need to listen to your mother. She stared at Sabra, who tried not to wobble. She wished she hadn’t left her bed. Clear this table, her mother said suddenly, and Sabra stumbled forward. Be careful with the glasses. One at a time, hold it with both hands. They cost a lot, you know. You don’t even know. Now a friend in her mother’s voice again, asking to play. How much do you think they cost? Sabra asked for the total. I think they were forty-nine? Forty-nine dollars, and the box came with six glasses. So? Each one cost eight dollars and sixteen cents! Are you sure? You don’t want to double-check? You can leave them in the sink for later. Bring the paper towels here. I’m so positive. But what happened with the remainder? They took turns guessing. It’s going on forever. It will never run dry. It’s ice-skating in outer space. It’s eating up all the food in the world. More than Foïla can ever eat. Her mother laughed. But what will happen at the end? Trick question, Mommy, because numbers don’t end, Mommy. Even if the number doesn’t have a period. Even if it looks like it ends. Even if it looks like nothing more than itself. Some people are like numbers, her mother said. Even if a person looks like nothing more than herself, know that she will never end. Even as Sabra believed it, she knew there was a part that sometimes tripped her up, but that night she told her mother yes, yes. Go get a new tablecloth.

Every person, she knew, loved even factors because they were easy to split and easy to join. They had no leftovers. She had known that all her life. But the numbers before her had begun to crowd the page and multiply. How did the numbers get their shape, she wondered. The loops of the eight, the openmouthed seven, the three with its puff of air, like it had been holding its breath forever. How many angles did they

Susanna Herrmann, Green Glass

hold? Who made these symbols? That was the only question she felt she could answer right then. She looked down at the curled swimmers pushing toward her, elbowing one another. She heard the pencil scratches of her rival next to her, and everyone else’s scratch marks, like squirrels pawing on a closed door. She was afraid to look up and get caught by the leader. Her head thrummed with hurt and hurt. You will never end, Mommy, she thought. We will never not be here.

“Ten minutes,” she heard the leader call out, but Sabra wanted the time to break now.

She gazed out the window, past the vines that had started to creep up the ground, toward the parking lot in the distance where their buses waited and a bus driver was palming the side of a bus like she was testing its strength with her own. Sabra glanced back down and took a deep breath. She did not know how she would look to her mother in the end.

“Five minutes.” The words heated her deep inside. She leaned into the desk to begin.

MELISSA BENECHE is a Haitian-American writer. She holds a BA in Creative Writing from Florida State University and an MFA in Fiction from Syracuse University. She was a runner up for the 2022 Cecelia Joyce Johnson Emerging Writer Award by the Key West Literary Seminar and has received residencies for her fiction from the Atlantic Center for the Arts, the Ucross Foundation, and Tin House. Her work appears in Bennington Review and SmokeLong Quarterly.